My Reading & Ideas

Some Coming Challenges

I like to run experiments. Indeed, I’ve written about this before. I had some time on my hands last week due to the Thanksgiving holiday and I decided to run some personal experiments of varying lengths during the next four months. The first month-long experiment is going to be writing in my journal every day in December. I usually write 40% to 50% of the days during a typical month.

During the middle of December, for ten days, I’m going to try and reach out daily to a friend of family member. This will be hard, because after a full day of interfacing with teenagers, I usually want quiet time to myself. However, as I get older I realize more and more that I need to make an effort to keep relationships going strong, or going at all. As the new year begins in January, I’m going to challenge myself to increase my daily meditation time above a certain threshold that will feel like I am stretching myself a bit.

Finally, once school is back in session after the winter break I am going to challenge myself to give a ‘Bronco Gram’ to a different one of my students for ten classes in a row, complimenting them for something very specific that they are doing well in class. That means Monday through Friday, a different student each day, two weeks in a row.

The direct impetus for challenging myself in the coming months came from author and blogger Scott Young’s ‘Foundations’ concept. Basically, Young came up with a list of what considers foundational elements of a good life and is offering classes around developing those foundations. I’m not taking his classes, but I loved the idea. I tweaked his list a bit and came up with 10 of my own that I want to keep top of mind in the coming year. My experiments around journaling and meditation stem from the foundation I am calling Spirit & Reflection. The challenge around contact with friend and family grow out my foundation of Connection. Finally, my challenge to dole out some written compliments to my students is connected to my foundation of Teaching & Work. I’ll occasionally give updates on how things are going.

Current Reading Stack

I finished three books this month, all of which I really enjoyed. Memoir is becoming one of my favorite genres. My current stack, as always, is heavy on the non-fiction and concentrated on history and psychology/self-help. I am slowly making progress on Blackhawk’s book, but not really enjoying it. I’m committed to finishing it, but it won’t get a high grade. On the other hand, I am really enjoying Johnson’s history of the world between 1815 and 1830. Learning a lot. The book about Hitchens will likely be finished next, so I am already having fun thinking about which book I’ll start next.

Universal Consciousness as Foundational Field?

I came across this very interesting study that attempts to help explain consciousness and bridge the gap between quantum physics, concsiousness research, and non-dual wisdom traditions. I can’t pretend to understand the math, but I understand the argument as articulated below and find it very interesting and seemingly inline with my understanding of Buddhism.

It also reminds me of Ken Wilber’s thought provoking AQAL ‘theory of everything.’ For instance, the study’s depiction of a “Pre-Big Bang” era aligns remarkably well with Wilber’s concept of Involution, where Spirit “descends” or involves itself to create the manifest world. Just as Wilber describes the formless Ground giving rise to form, the study proposes a mathematical “collapse mechanism” initiated by Universal Thought that transitions ‘undifferentiated potential’ into specific physical states. Crucially, both frameworks agree that space and time are not fundamental containers, but emergent properties that arise only after this initial descent occurs. Consequently, the study offers a potential physics-based model for Wilber’s philosophical claim that the spatial-temporal universe is a secondary creation of a deeper, non-spatial consciousness.

My personal bias has me rooting for studies like this. If core Buddhist concepts can be validated with math, that’s a win. Also, if consciousness is unified, then it is true that our feeling of separateness is indeed an illusion. It also reinforces the Buddhist conclusion that we should have compassion for all living beings, animals included, because we are literally cut from the same cloth. All in all, very interesting. I hope more related inquiries follow.

Hope

I came across this quote in the recent George Packer “By the Book' segment in the New York Times. I love this sort of thing because I love seeing into the unique details of other people’s lives. It’s the same reason I love the weekly ‘Sunday Routine’ segment they do.

Randomly, I actually had the pleasure to meet Mr. Packer when he came to my school to talk about reading and writing to several classes (including mine). I think it was 2019?!? I’ve enjoyed the three books of his that I’ve read, including The Assassins' Gate, The Unwinding, and his biography of ambassador Richard Holbrooke, Our Man.

What might I add to this excellent, succinct list? Other than swapping his progeny out for mine, not much: Packer nailed it.

On Christopher Hitchens

I am reading an interesting book about one of my intellectual heroes, the late Christopher Hitchens. The book’s author, coming from the political left, argues that Hitchens got a lot right, but erred seriously in his support for both the “War on Terrorism” and the Iraq War during the first decade of the 21st century. Hitchens began his intellectual journey as a socialist and by 2004 was oddly all in on Bush’s foreign policy in the Middle East. The author also critically deconstructs some of the arguments Hitchens' made in debates about religion.

A couple points come to mind as I reflect on Hitchens and his thinking. For one, his mistakes make him more—not less—useful to thinkers today. The book emphasizes that studying where Hitchens went wrong sharpens our own judgment. Heroes aren’t templates; they’re case studies. His intellectual courage, eloquence, and range remain valuable, but so do the cautionary lessons that grew from his rhetorical confidence and general arrogance. Additionally, I am reminded that admiration doesn’t require full agreement about everything—especially with complicated figures like Hitch. Indeed, there is no one I likely agree with on everything. In my mind, Hitchens' error about Iraq does not tarnish his overall body of intellectual work. For instance, I love his book god Is Not Great, but thought his attacks on Buddhism to be feeble and a wasted effort.

But none of this diminishes Hitchens' importance. If anything, it makes him more useful. Hitchens shows us that admiration doesn’t always require absolute agreement and that inspiration doesn’t require perfection. For me, he remains a case study in how a thinker can be both brilliantly right and consequentially wrong—and still worth reading, wrestling with, and learning from.

Odd and Unpredictable

Bruce Dickinson is one of the most fascinating people in the world. He is most famous for being the long time lead singer of Iron Maiden, one of the best heavy metal bands of all time. However, in addition to that, Dickinson is also an author and a pilot, eventually flying the band around the world on their tours on their plane, Ed Force One. He is also a world-class fencer! His wide-ranging intellectual interests can be seen in the songs he has written over years. For instance, Alexander the Great is a great history lesson and Rime of the Ancient Mariner a great homage to Coleridge’s epic poem of the same name. Hell, I was first introduced to the novel Dune because of Maiden’s tune To Tame A Land.

The quote below is from his memoir What Does This Button Do? I saved it because I thought it was a great sounding sentence. I also saved it because I manages to convey a complex reality, very neatly.

On Travel

I agree whole-heartedly with Ryan Holiday’s take on Didion’s quote. I consider myself extremely fortunate about my travel experiences thus far. Indeed, I would even say I am relatively well traveled. That said, most of my close friends have seen more of the world that I have.

I didn’t really travel beyond California until I was in college. I roadtripped with parents once to southern California. Freshmen year I drove out with a friend to Utah. It wasn’t until I went to England for my junior year abroad that I really ‘traveled.’ Luckily, I was able to see a lot of Europe that year. Besides the big cities, I have very fond memories of Bedous, France and Korfu Island, Greece. Since then, memorable places I’ve visited include Chang Mai, Thailand and driving the Al-Can Highway from Portland up to Anchorage.

Having friends that are so well traveled helps keep the travel bug alive. Hearing about their advantures motivates me to keep checking places off my list. My Top 5 list at the moment (it is always changing, of course) of places I want to visit include: 1) Quebec City 2) Nova Scotia 3) Copenhagen 4) Sydney and 5) Anywhere in New Zealand.

Thinking about traveling, I realize there are certain parts of the world I’m just not that interested in visiting. I don’t know what that says about me, but it’s true. I suppose I wouln’t ever turn down an opportunity to go to one of these places, but with so many places to visit, there are definitely tiers of interest that are real for me.

Didion’s quote also lands because it connects with parenting in my mind. I feel like it is a duty of a parent to try and expose their children to as much travel as they can afford. The reason, in my mind, is connected with the argument Holiday was making with Didion’s quote in his book about wisdom. Specifically, seeing other parts of the world, experiencing other cultures, and meeting different people all help us become more wise as we become less insular.

Choose Your Hard

This quote is a major truth bomb, one we all need to remember. Hard is inevitable. Most of us operate under the illusion that if we take the easy way out, there will be no consequences. This is most often not the case. Indeed, in areas such as our health and finances, the consequences of poor choices can be devastating.

For me, making the right choice regarding exercise is most challenging. I have all the excuses in the book, but I know that if I don’t get my heart rate up every day (or most days), that I will pay the price in my 60s and beyond. Indeed, as I write this, I am experiencing some lower back issues. Why? Because I usually put off stretching and working on my core.

Teaching has its share of challenges in this regard, as well. For instance, parent outreach is frustrating for a variety of reasons, but I have learned that making the attempt, even if I never make contact, smooths out future interactions with both student and the parent.

Eventually I realized that if I wanted to choose the harder-but-better path, I needed habits that made the choice easier. These practices include reading widely, tracking certain metrics (like what I eat and drink, my weight, my steps, how many minutes I exercise each day), and meditation. Together, these habits help slow down my decision making and provide unvarnished data about how I am doing. Indeed, these three practices alone have provided a huge ROI for me. I know for a fact I’d be worse off without having them in my habit toolkit.

Blogging every day is another example of ‘choosing my hard.’ My posts aren’t long, but I’ve committed to putting something out every day and it isn’t always easy. However, I know that at the end of my blogging journey, I’ll be a better writer, a clearer thinker, and will be able to take pride in doing something I always wanted to do. Hard is inevitable, but when I choose it on purpose, it becomes a path instead of a burden.

What the?

I teach in a public high school so I hear cuss words pretty regularly. I also happen to cuss a fair amount myself, though hopefully not often in earshot of others who might be offended. When I come across the f word in a book, it doesn’t faze me much. It is usually used in an appropriate context and I treat it like any other word.

Recently while reading Bill Belichick’s book On Winning, he redacted the f word in a sentence. I was a bit aghast. As a football coach, I’m 100% sure he cusses regularly and probably does it more than a typical person at work, given his job as a coach of professional (and now college) football players. Honestly, I thought it was pretty lame. Who does he think is reading his book? Who is he trying not to offend? Indeed, to me it was self censorship on behalf of the type of guy who is into football but gets offended by ‘bad words.’ The feelings of such a snowflake should not take priority. Overall, though this is an inconsequential take, it is a lame move in my book. It treats the reader like a child. Just say what you mean, Bill. When the word is redacted but has the ‘f’ in front, the word still appears in the mind of the reader, after all. The redaction doesn’t really work.

Now, Diane Ravitch on the other hand, isn’t afraid to include a four letter word like the f word in her memoir. She is actually quoting the civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, but the fact that she treats her readers like grown ups is appreciated. Also, considering the context, the word’s use is appropriate. Fuck nazis, right?

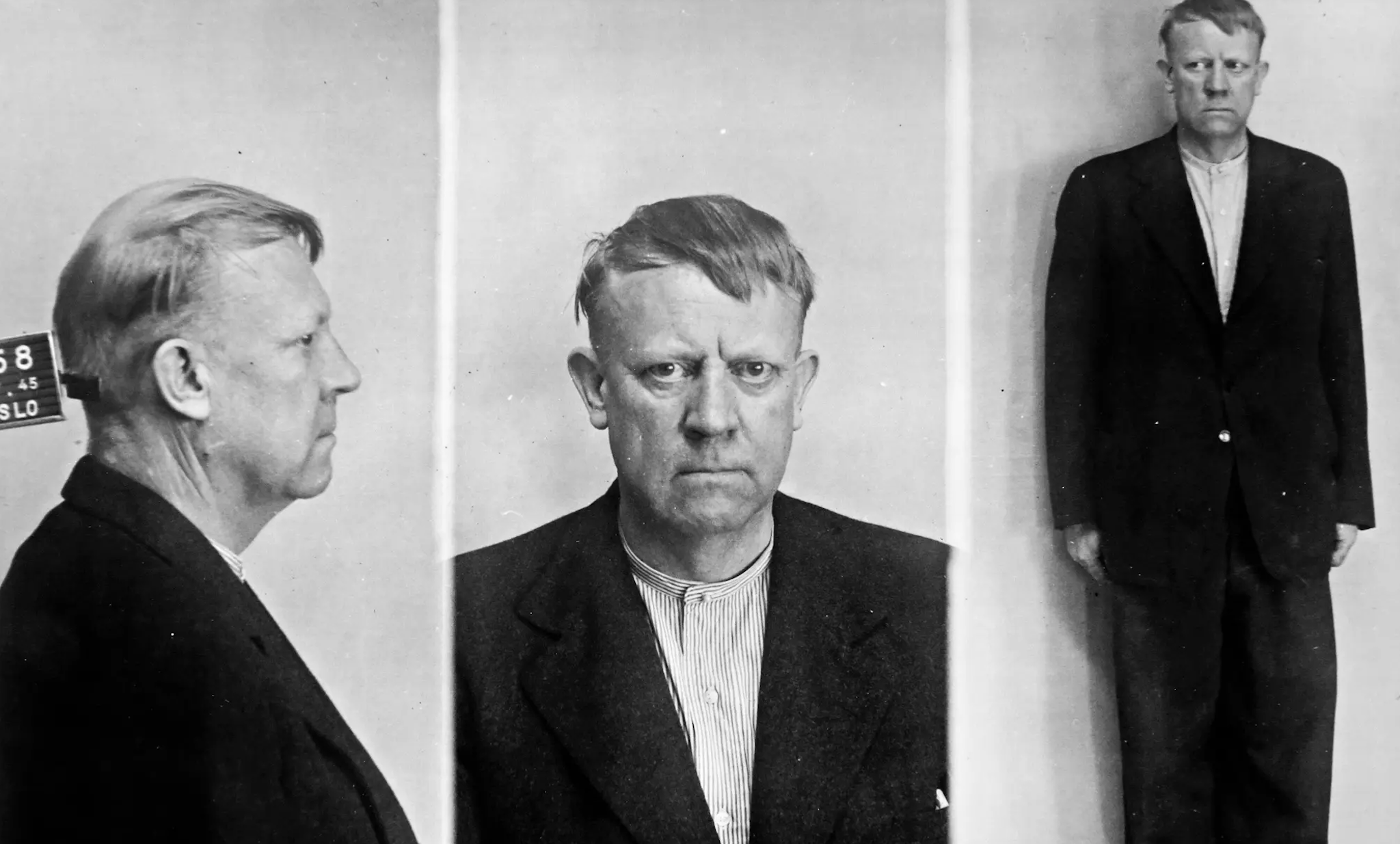

What or Who is a Quisling?

In Diane Ravitch’s memoir An Education, which I am thoroughly enjoying (!), I came across a word I was not familiar with. The word is ‘quisling.’ Chat bots being my new reading companions, I quickly looked it up.

The word is of relatively recent vintage, being coined during World War II. Apparently, a Norwegian fascist named Vidkun Quisling collaborated with the Nazis in his home country during the war. Thus, the word refers to someone who betrays their own country, or own group, by collaborating with the enemy. Benedict Arnold came to mind immediately when thinking about this. Thus, a quisling is a traitor. **Great word! **

Not surprisingly, Quisling was put on trial after the war for a variety of crimes and was found guilty. He was executed by firing squad in October 1945 in Oslo. He was buried in an unmarked grade, and his surname now is equated with treachery. A fitting end, I’d say.

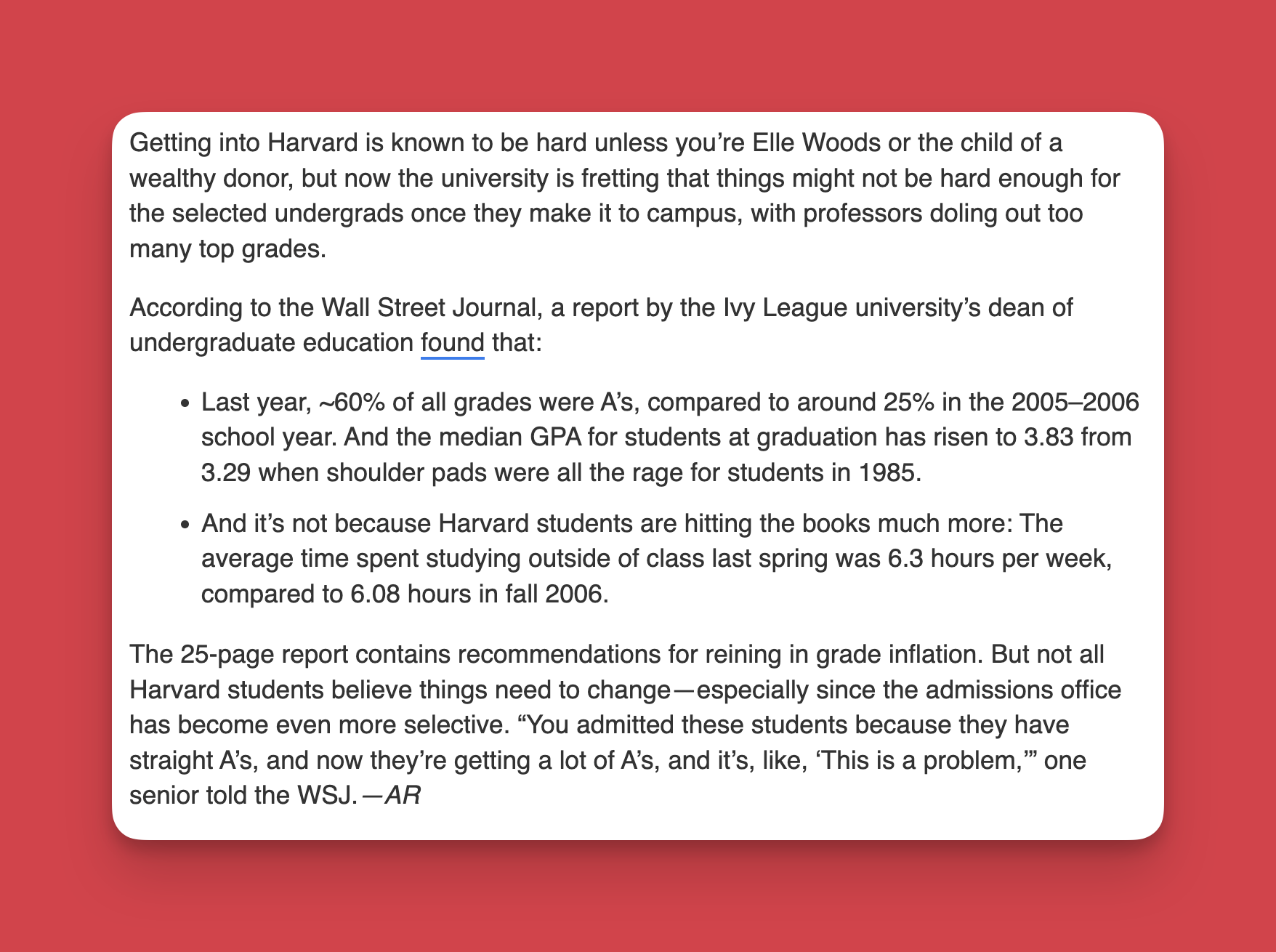

On Grade Inflation

I came across the information below in today’s Morning Brew newsletter. It appears professors at one of America’s most elite universities are inflating grades. Shocker! Indeed, I don’t buy the comment from the student quoted at the bottom of the screenshot. College should be much more difficult than high school and just because a student earned A’s in high school, that shouldn’t necessarily mean they will deserve the same grades in college.

In fact, as a high school teacher, approaching three full decades in the classroom, I can say emphatically that high schools are also inflating grades. In the case of high schools the reasons for this include the incentive placed on schools to increase graduation rates and ‘equity.’ Neither of these root causes are positive developments, yet they are the current reality, at least where I teach.

Whether or not this all matters is worth thinking about. Here are a few takes on the topic: Take #1 and Take #2. The problem I have with it is that it warps the connection in the minds of students between their efforts and the quality of the outcomes of their efforts. In all of life, feedback is data. If the feedback is inaccurate, it puts people at a disadvantage as they move through early adulthood. The disconnect can lead to some serious pain (like borrowing tens of thousands of dollars for school and then flunking out). For kids coming from middle and working class families, they deserve honest feedback in the form of grades.

Privilege is a flip side to this. Many people whose lives and outcomes are boosted by privilege face the same problem of disconnect between effort and outcomes. Often their success had little to do with their efforts and a lot to do with the privilege they inherited. Considering that approximately 57% of Harvard students come from families in the top 10% of the income distribution, it is clear this is relevant give the grade inflation there.

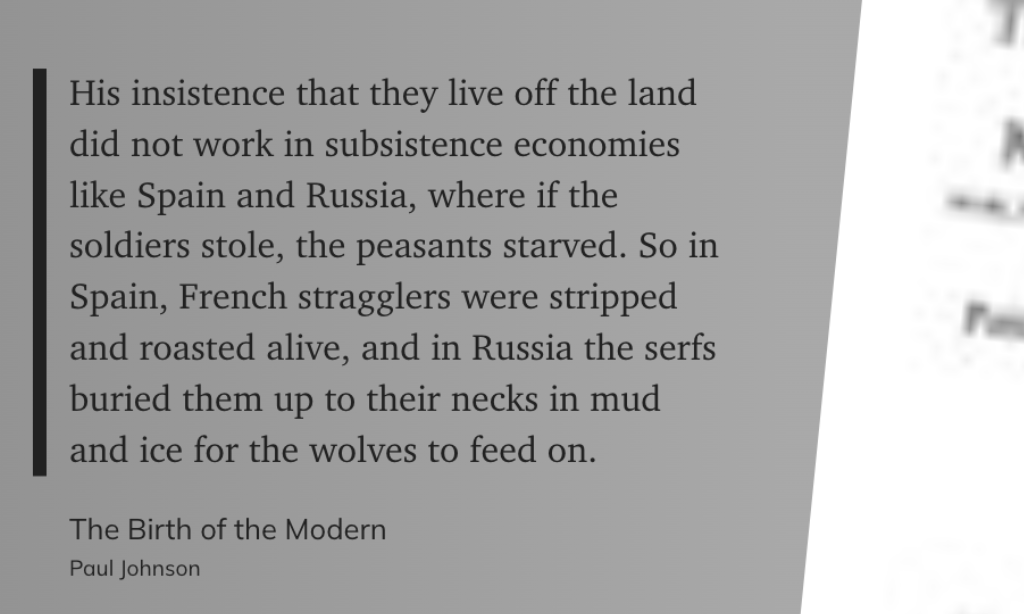

Remembering the Human Cost

Napoleon’s soldiers learned that “living off the land” often meant making others starve. Those soldiers were mostly conscripts who had no choice but follow orders and face the gruesome consequences. In America our veterans are volunteers, yet they still know better than anyone that war is not abstract—it’s human, filled with folly and unimaginable human suffering. This Veteran’s Day, let’s honor not only the bravery of those who serve, but their deep understanding of what war actually asks of them, and the world.

Shaka Zulu

I recently came across Shaka ka Senzangakhona in three different books over the past two weeks, and I found his story too striking not to share. I first came across him in The Narrow Corridor, where the authors discuss his unique military innovations and brutal, but successful leadership. A few days ago, he appeared in General Stanley McChrystal’s book On Character. McChrystal shared a story about how Shaka made his warriors dance on ground covered with sharp needles and if they flinched, they were executed. Finally, in The Birth of the Modern, he was brought up in the context of the history of southern Africa during the early 19th century, when he reigned. I love it when such serendipity pops up in my reading.

Anyway…born around 1787 and dying in 1828, Shaka became king of the Zulu in what is now KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa from 1816 to 1828.

What fascinates me is how he took a relatively minor clan and, through bold military, social and political reforms, built it into a dominant power in his corner of Africa. His success arose because he reorganised the Zulu regiments, introduced new weaponry and tactical formations, and absorbed neighbouring groups under Zulu rule.

At the same time, Shaka’s reign is drenched in blood and controversy. His mother’s death in 1827 triggered a wave of harsh decrees—including mass-executions, bans on planting or using milk, and demands of mourning—that turned many of his own people against him. He was also apparently so paranoid that his heir might depose him, that if any of his concubines became pregnant, he had them killed. Not surprisingly, he was assassinated by his half-brothers in 1828.

In my reading, I’ve found myself wondering: how do we reconcile the visionary-leader and the ruthless-tyrant in one figure? His life makes me think of people like Alexander the Great and Napoleon, who are often idolized, but who both caused tremendous suffering as a result of their military pursuits. I’ll continue to reflect on how each of the three authors portrays Shaka, as successful military leader and cruel tyrant, and invite you to do the same. How does his story challenge our ideas of leadership and legacy? What lessons (or warnings) does his rise and fall offer us today?

Sui Generis

I recently came across a term I wasn’t familiar wtih–sui generis. Upon reflection, I know I’ve come across it before, but maybe only once or twice in all my reading and I had to look it up to learn what it meant. The phrase means ‘unique’ or, more technically, ‘of its own kind.’ It is Latin. It’s used to describe something that doesn’t fit neatly into existing categories; something truly original. Philosophers often use it to describe phenomena that are irreducible — things that can’t be fully explained by reference to anything else, such as consciousness. In music, I suppose Miles Davis' Bitches Brew fits the description. Certainly every psychedelic experience is sui generis, as language tends to fail in its usual ability to accurately describe.

Of course, each of us, and each sober, conscious moment is also sui generis. This is hard to see sometimes because we automatically sort everything we come across. We categorize. Our brain does it to help us survive and it is hardwired into us. However, beneath the categories are unique moments, perceived by unique people. Indeed, we are all mavericks and ultimately uncategorizable. In times like these, when our politics leads us to stereotype and heap people into convenient groups, this ancient concept reminds me to try and see differently. It also encourages us to revel in our peculiarities, as Ursla K. Le Guin said.

Right and Left

I treated myself today to a long browse at Powell’s downtown. I walked out with two books, neither of which I had on my radar going in. I noticed after I left that the two books had a something in common: They are both books about American intellectuals who at various times in their lives took positions that didn’t align with their initial ideologies. In the case of education expert Diana Ravitch, her views morphed from conservative to liberal over her adulthood. In the case of Hitchens, who is one of my real intellectual heroes, he was a loud supporter of America’s war in Iraq, despite his position leading up to the war as a staunch leftist. He didn’t become a conservative, but he took a controversial position that rankled many on the Left that previously tended to agree with him.

Patriotism trumps Nationalism

In my APUSH classes today we wrapped up the War of 1812 and began a lesson on the surge of nationalism that arose in the young United States in the wake of the war. To help differentiate nationalism from patriotism, I shared the quotes below from Roger Cohen’s excellent, thought-provoking book An Affirming Flame and encouraged students to discuss them.

My students got Cohen’s points immediately, and I think it is safe to say they agree with Albert Einstein that nationalism is an ‘infantile disease’ that leads to war and is primitive and unbecoming of grown ups in this day and age. Many of us can see that now. However, nations as political constructs are not all that old and despite the fact that in the early 1800s the Napoleonic Wars were raging in Europe, the horrors of the two world wars lay ahead of everyone. The nationalism that arose in America during and after the Era of Good Feelings had many contributing factors (such as the Battle of New Orleans, Clay’s American System, Chief Justice John Marshall’s SCOTUS rulings, and developments in the arts) and in hindsight it is understandable why it arose. However, surely it is time to put the ridiculous ideology to bed and replace it with an openhearted patriotism and general goodwill towards others.

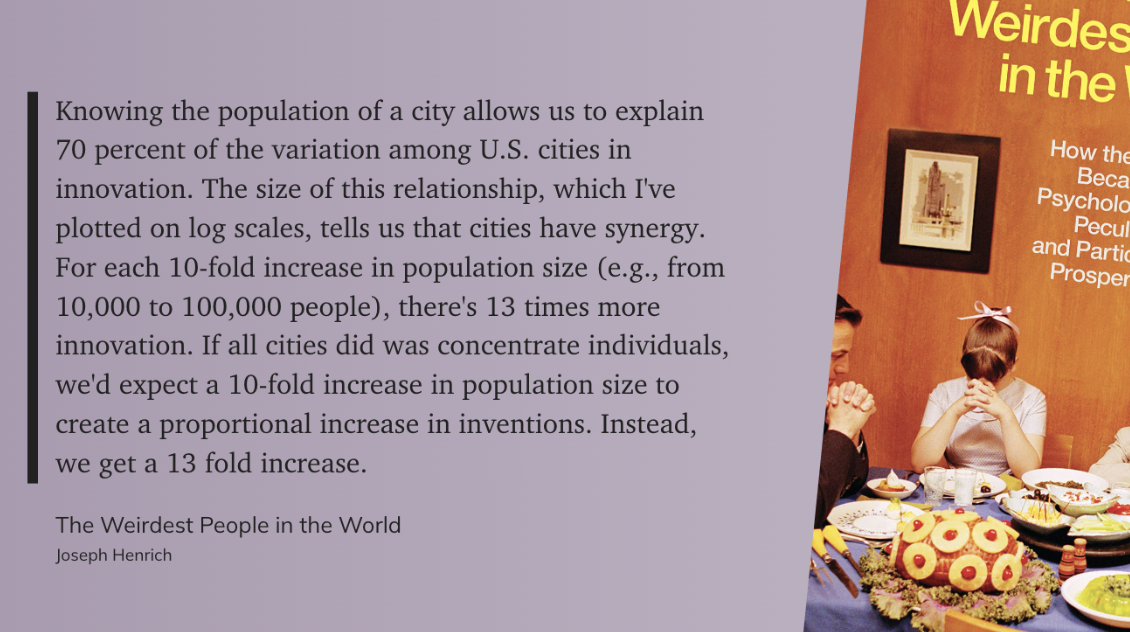

Huzzah to the Big, Beautiful City

New York City made history yesterday electing immigrant politician Zohran Mamdani as their new mayor. It got me thinking about New York, which is a city I love and have been fortunate to visit many times (and will soon be visiting again). Then this morning, the quote below appeared in my daily Readwise email. The quote is from The Weirdest People in the World by professor Joseph Henrich. The quote notes the fact that big, beautiful, diverse cities like New York are more innovative than the sum of their parts. I think many of us intuit this, but in the book Henrich explains the research and the logic. However, innovation isn’t the reason I love places like New York, but it is adjacent to what I love–the vibrancy, the opportunity for serendipity, the randomness, the deep layers of culture, and the variety of experiences available.

These admirable and enjoyable elements of modern urban life contrast vividly in my mind with what I see when I drive through rural America. I’m always shocked by how depressed and poor rural America feels. Small town America just gives off defeated vibes to me. I don’t mean to insult people who live in rural places. I’m only expressing my reaction when passing through and I am certainly not condemning or criticizing people who prefer to live in rural areas. To each his own.

Nevertheless, the point Henrich makes with this quote, and in his book generally, is that cities drive innovation and progress. As a fan of diverse, electric places like New York City, I’m not surprised.

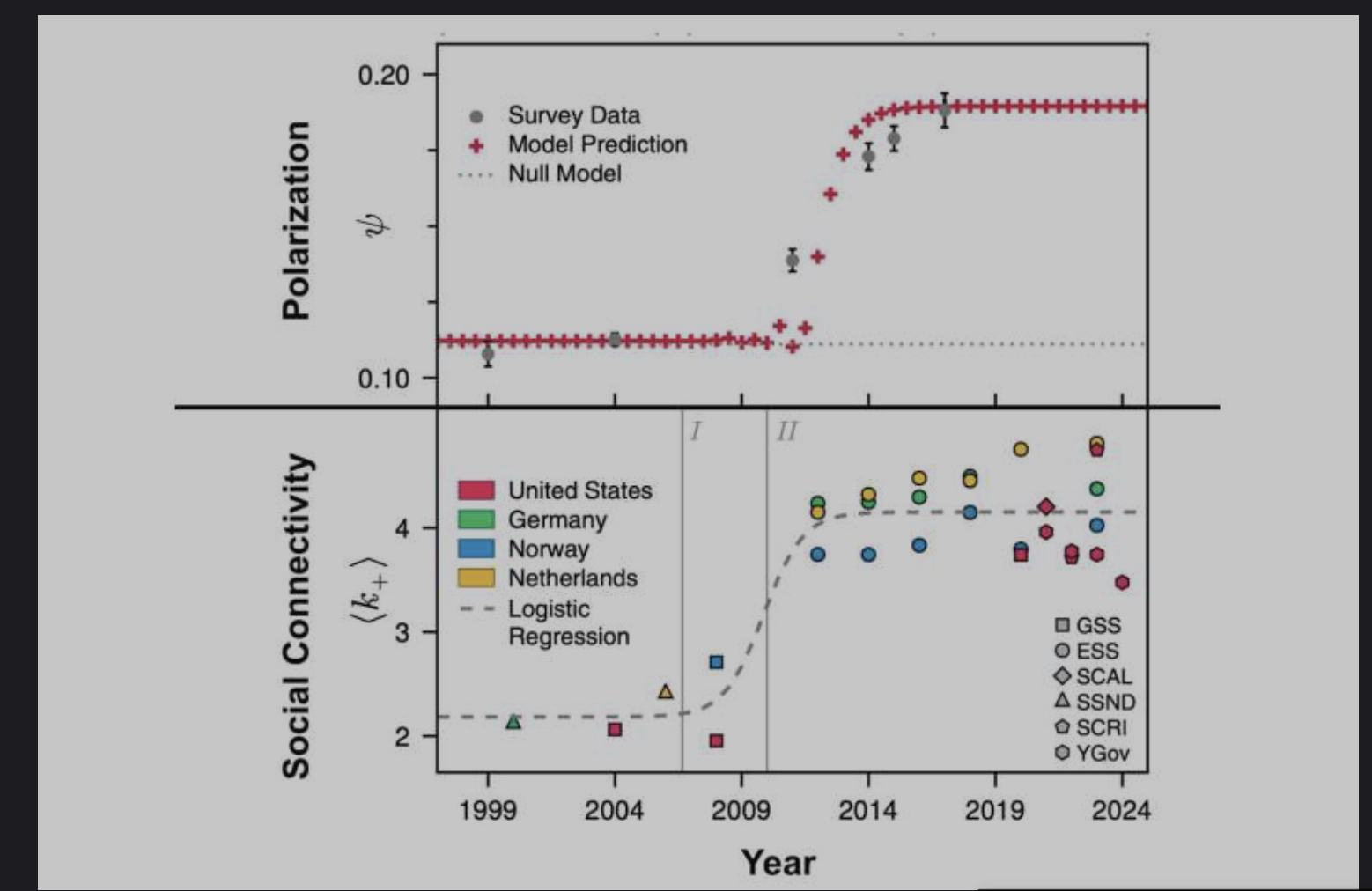

More Friends, More Division?

This research makes a few points that are interesting, relevant, yet slightly counterintuitive. According to this article, by Complexity Science Hub Vienna, the number of close friends people have has increased over the past fifteen years (starting between 2008 and 2010). This coincides with the rise of smart phones and social media. However, political polarization has also increased. According to the article, those consistently expressing liberal views rose from 14% to 31%, while those holding conservative views increased from 6% to 16%. The researchers explain that since most people have more close friends, they are more likely to cut ties with one who has different political beliefs then they do. That means more of us have friend groups that see the world they way we do politically. In other words, there are less ‘bridge friends’ who help expose us to different viewpoints. The end result is less dialogue and more breakdown of our democracy, both of which are becoming enormously dangerous at present.

Another interesting angle has to do with Dunbar’s number, which suggests we can only maintain about 150 meaningful relationships, with roughly 5 close friends in our innermost circle. This research shows we went from 2 close friends to 4-5 around 2008-2010—so we’re actually approaching the upper limit of what Dunbar predicted for our intimate circle.

Thus, it can be said we are not exceeding our cognitive capacity for friendships; we’re just filling it differently. Social media didn’t give us superhuman social abilities. Rather, it made it easier to maintain more connections within our natural limits. But here’s the problem: when you’re at capacity with like-minded friends who are easy to maintain online, there’s no room (or motivation) for the harder work of bridging divides with people who think differently.

In other words, Dunbar’s Law explains why the doubling of close friends leads to polarization: we’ve hit our cognitive ceiling, so we’re now optimizing for similarity and comfort rather than diversity. Our social “budget” is maxed out on echo chambers.

Some Thoughts from Retired General Stanley McChrystal

General Stanley McChrystal is a fascinating dude. I first learned about him when he was forced to resign by Obama in 2010 because of comments attributed to him and his staff members that were published in Rolling Stone. Leading up to that, I have learned that he was a top rate soldier, which explains why he was in charge of Allied forces in Afghanistan at the start of Obama’s presidency. His military career is undoubtedly honorable and exemplary.

He is also known for the fact that for many years while in the military he only ate one meal a day. Combined with his daily exercise regimen he developed a reputation, even amongst those in the military, as a Spartan.

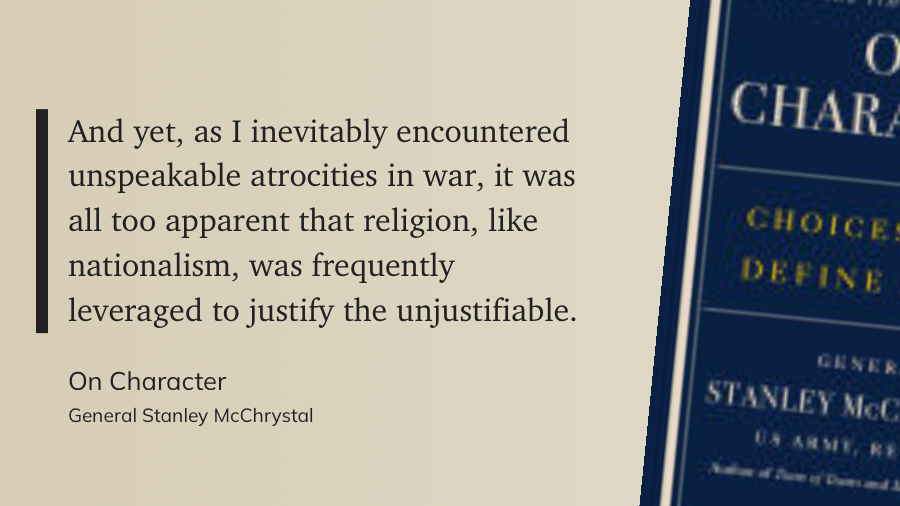

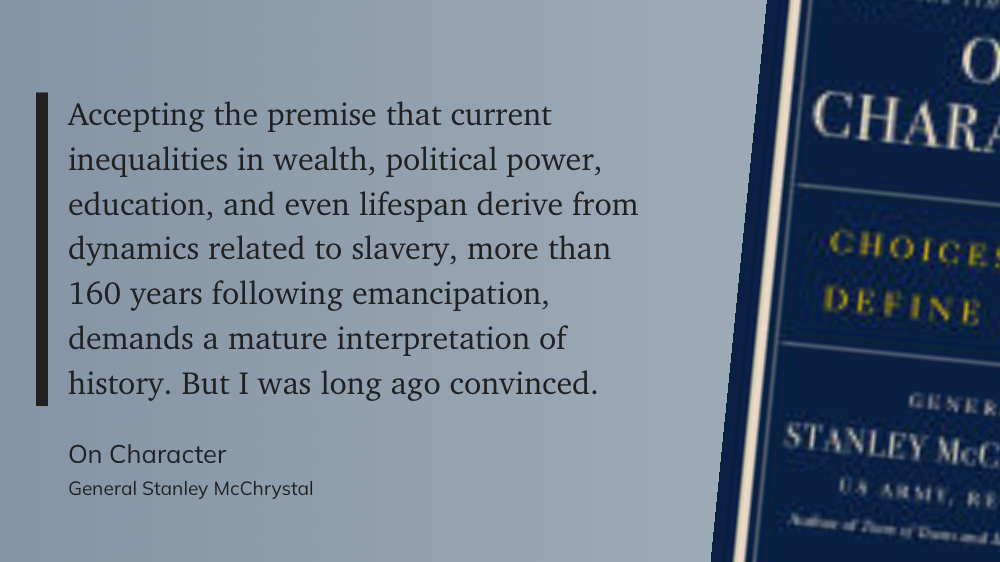

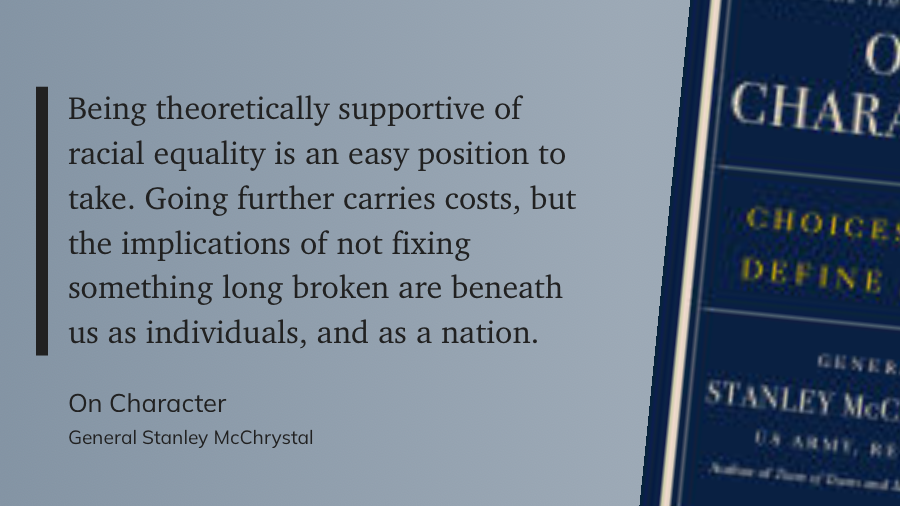

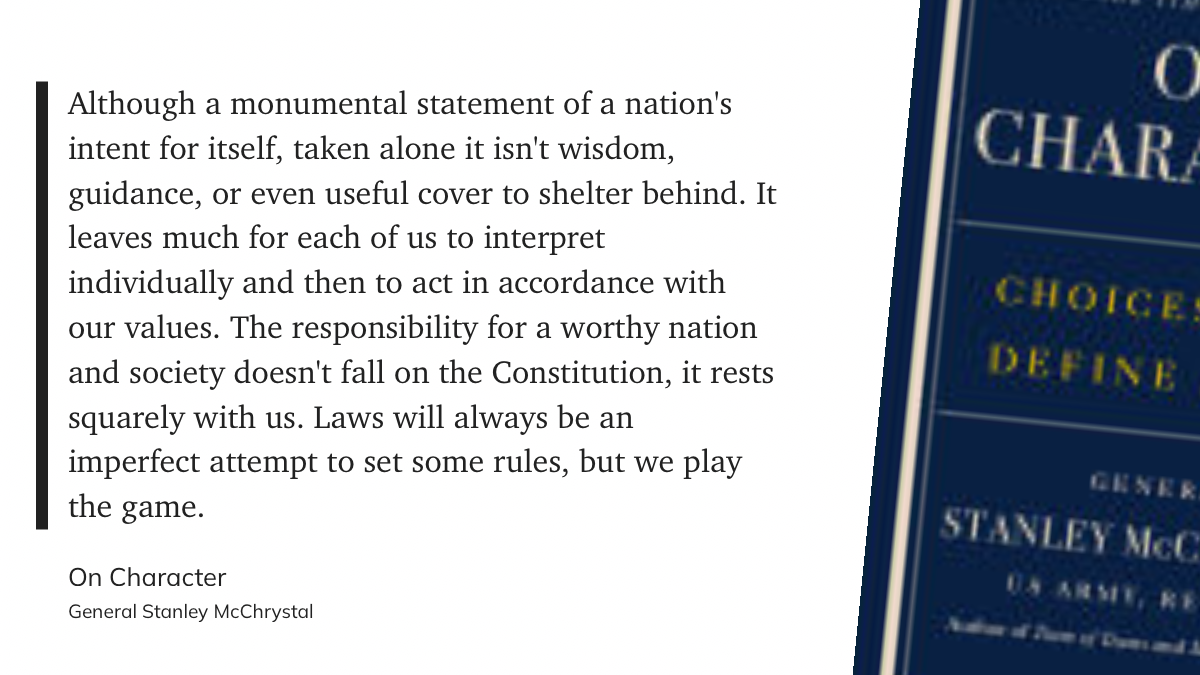

I am currently reading his book On Character and enjoying it very much. McChrystal is clearly a thoughful guy and not easily pigeonholed. I find myself agreeing with most of his takes on the big issues he discusses in the book. Below are some of his thinking, which I found insightful and wise. The quotes are about religion (1), race (2 & 3), and the Constitution (4).

You Know What's Really Scary?

There is a lot of scary realities about America right now. Here are a few such examples.

-

Approximately 42 million people need SNAP benefits to help them get through the month.

-

Roughly 34% of U.S. fourth graders cannot read at a basic level, and gaps between low-income and high-income students are widening (National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2023).

-

The richest 10% of Americans own nearly 70% of all wealth, while the bottom half collectively holds just 2.6% (Federal Reserve), 2023). That’s the widest gap since the Great Depression.

-

The U.S. has experienced over 600 mass shootings each year since 2020, averaging almost two per day (Gun Violence Archive, 2024). Firearms are now the leading cause of death for children in America.

-

Nearly one in three teens report poor mental health most of the time, and suicide is now the second leading cause of death for people ages 10–24 (CDC, 2023)