Teaching and Learning

The Kids Are Alright

My school has a hybrid schedule. Two days a week the periods are 90 minutes long. I usually take that opportunity to start those longer classes with what I call a ‘whip around’ question. These questions are meant to let everyone share their thoughts and for me to get to know my students better. This week I asked my students ‘What is something that you are really into right now?’ I got a wide assortment of answers (from new TV shows, to baking, to taking walks at night), including references to music. To my delight, in my 7th period class four students mentioned listening to the Grateful Dead. This was an amazing surprise, though it makes sense in the wake of Bobby Weir’s recent passing. It goes without saying that I was stoked to be able to talk about my love of the Dead for a few minutes. Students even asked if I’d shared some Dead tunes in Google Classroom. (Mission accepted!)

Another thing that recently happened at my school happened today. One of my former students, who is now a senior, organized a walkout and short march from our school to the district office. The whole thing lasted about an hour, but about 400 students participated. Needless to say, it is encouraging to see young people engage politically within the growing authoritarian environment we are all experiencing in the United States.

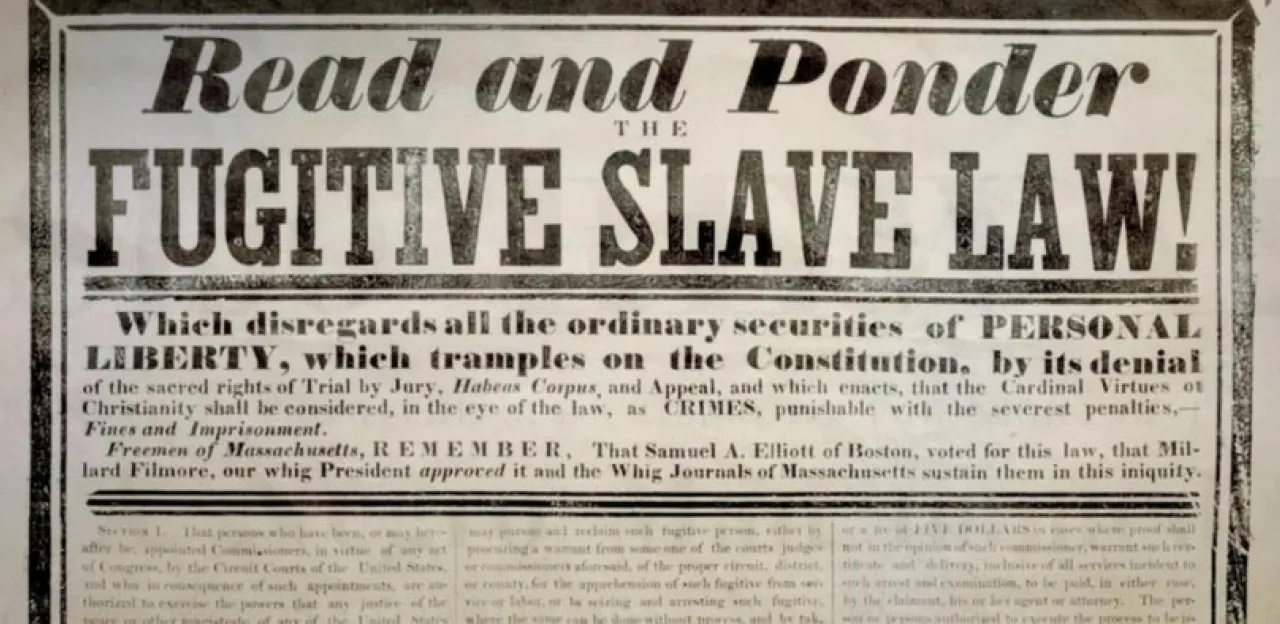

A Connection with the Past

I am teaching my students about the coming of the American Civil War. Today we read about and discussed the Compromise of 1850 and the attendant Fugitive Slave Law. Considering we are two days out from the murder of Renee Nicole Good and a day out from federal agents having shot two people here in Portland, students made some connections. Of course, some of my students are currently quite frightened by what is happening in our country. Others are seething. I noticed that it was quite easy for them to understand the anger and outrage northern abolitionists must have felt in the 1850s, when their federal government was behaving in such a patently immoral way. Unlike any other year that I have taught this, students are connecting in a unique and powerful way.

You might say events, along with an understanding of the past, are waking them up.

Exciting News for My School

I found out today that our school is going to be visted by Ketanji Brown Jackson, one our country’s nine Supreme Court Justices. As an AP Government teacher this is thrilling. We just finished learning about the judicial branch last week and all my students know who she is. I’ve had (now retired) congressmen Earl Blumenauer visit my class before, and early in his presidency George W. Bush gave a speech in our gym (I was conveniently out of town for that). The Justice will be visiting in March as part of a book tour to promote her recent memoir Lovely One.

Ketanji Brown Jackson was appointed by President Biden in 2022 and is the newest Justice of the Supreme Court. She’s a fellow Gen Xer who grew up in Miami, Florida and was raised by two teachers. She earned her Bachelor’s and her Master’s degrees from Harvard and served as a supervising editor of the Harvard Law Review. She replaced Justice Stephen Breyer whom she had clerked for previously. She is also the first SCOTUS justice to have been a public defender. She is also the first African American woman to serve on the Supreme Court.

Since being on the court, she has stood out for being willing to ask a lot of questions during oral arguments. By contrast, longest serving Justice Clarence Thomas went 10 years without asking a single question from the bench (from February 2006 to February 2016). Justice Brown Jackson has also written 8 solo dissents thus far, an unusually high number. Finally, students of the Supreme Court have described her as pushing ‘progressive originalism.’ Conservatives tend to stake a claim to ‘originalism,’ which is a reading of the law that harkens back to the supposed ‘original’ intent of the founders. In Justice Brown Jackson’s case, she has harkened back to America’s ‘second founding’—the Reconstruction Era–and especially the 14th Amendment to argue in favor of ideas such as affirmative action.

Needless to say, I’m stoked to see her speak in person in the spring.

On William Penn

Most of us remember that Pennsylvania was founded and named after William Penn. Many will also recall that Penn was a Quaker and that the Quakers were a Protestant Christian sect that were pacifist and later played an important role in the abolitionist movement and the underground railroad. Oregonians may know that one of our local universities is named after the leading Quaker George Fox.

Penn comes up in my AP US History class when students are learning about the unique attributes of the original British colonies in America. I always talk a little about the Quakers and note that the city of Philadelphia derives its name from the Greek words for ‘dear’ or ‘loving’ and ‘brother.’ Hence, the ‘City of Brotherly Love.’ Very Penn.

I also instruct my students that Penn was relatively warm to the indigenous tribes. His general kindness backfired however, in the sense that migrants to the colonies found Pennsylvania relatively welcoming since the founder was so tolerant. The result was, after Penn’s death, the arrival of many who were not so tolerant, ultimately dooming the Native peoples to similarly frustrating sorry relative to the other parts of British North America.

However, I recently learned through my reading that Penn actually took the time to learn the language of the Lenni-Lenape (Delaware) people in order that he would be able to more fairly deal with them (he already knew five other languages, including English). Penn removed the middle man, hoping for deeper understanding and more fair dealing. I found this to be quite incredible, given what we know about the other colonists and their general greed and avarice. Indeed, Penn’s respect for the natives led to the so-called ‘long peace’ in Pennsylvania which lasted throughout his lifetime.

Using Notebook LM in Class

I have been experimenting as a teacher with Notebook LM. One of the cool things we can do is create our own ‘notebook’ with our own hand selected resources, and then share them with our students. Student can then use the ‘notebook’ to study. For instance, they can have the tool quiz them based on the content in the ‘notebook.’ They can also make a concept web and then click around to review details. Another cool feature, which has been out for a while now, is being able to make a podcast that reviews all the content in the ‘notebook’.

My APUSH students will be taking an exam soon on the period 1800 through 1848. I compiled a ‘notebook’ that included hand-selected YouTube videos, websites, and even my own lecture notes. It took the software about 2 minutes to make a 14 minute podcast conversation reviewing all the content in the ‘notebook.’ Pretty damn cool! The podcast is here if you want to check it out.

My same students are also having a seminar on an essay about Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831. Because I have a pdf of the essay, I was able to turn that into a podcast, as well. My plan is to share that with the kids after their seminar, as I don’t want to discourage them from doing the reading.

A new feature that hasn’t quite rolled out to schools yet is infographics. All together, this is an amazing new tool for high school students, and for lifelong learners.

Nano Banana Pro Revisited

Yesterday I wrote about my disappointment with the latest version of Google’s image generator, Nano Banana Pro. I decided to ask Gemini what I was missing and lo and behold, it explained to me what I was doing wrong. I also realized that the best way to make infographics, which I’ll want to do for my students, is to use Notebook LM, not Nano Banana.

Here are a couple of pics I created for my next lessons in AP Gov and APUSH. We are looking at the New Deal and Great Society in AP Gov and Nat Turner’s Rebellion in APUSH.

Pretty cool.

Playing Around with Nano Banana Pro

I am interested in the latest tech and decided today to play around with Google’s new Nano Banana Pro, which is the top of the shelf (for now) AI image generator. Since it landed a few days ago, there are a lot of YouTubers showing off the potential use cases.

The first image I worked on was a simple, but custom infographic comparing the New Deal and the Great Society for my AP Gov class. Students are working in pairs to conduct the initial reasearch, but I wanted a visual for our review. I’m pleased with the results, but not blown away.

I then decided to see if I could get a picture of FDR and LBJ in the front of my classroom so I could include it on our next daily agenda. I uploaded a photo of the front of my room. Unfortunately, it couldn’t handle my request. For one, it couldn’t use the photo I uploaded. Instead the image it created used a made up, generic classroom. Secondly, it wouldn’t make images of FDR or LBJ since they are ‘public figures.’ Disappointing, but understandable.

Finally, I asked Nano Banana Pro to make a timeline infographic of 10 major uprisings in American History (we are about to have a Socratic seminar on an essay about Nat Turner). It did an alright job, but included two of the events twice. I asked it again to remake the infographic without the duplications and it duplicated _all _the events. Very disappointing. It makes me wonder how much the YouTube influencers are getting paid by Google to promote a product that isn’t quite as good as advertised. Even if they aren’t paying them, surely they are boosting the algorithm (since they own both YouTube and Nano Banana). Needless to say, I don’t imagine using this tool much in the near future.

On Grade Inflation

I came across the information below in today’s Morning Brew newsletter. It appears professors at one of America’s most elite universities are inflating grades. Shocker! Indeed, I don’t buy the comment from the student quoted at the bottom of the screenshot. College should be much more difficult than high school and just because a student earned A’s in high school, that shouldn’t necessarily mean they will deserve the same grades in college.

In fact, as a high school teacher, approaching three full decades in the classroom, I can say emphatically that high schools are also inflating grades. In the case of high schools the reasons for this include the incentive placed on schools to increase graduation rates and ‘equity.’ Neither of these root causes are positive developments, yet they are the current reality, at least where I teach.

Whether or not this all matters is worth thinking about. Here are a few takes on the topic: Take #1 and Take #2. The problem I have with it is that it warps the connection in the minds of students between their efforts and the quality of the outcomes of their efforts. In all of life, feedback is data. If the feedback is inaccurate, it puts people at a disadvantage as they move through early adulthood. The disconnect can lead to some serious pain (like borrowing tens of thousands of dollars for school and then flunking out). For kids coming from middle and working class families, they deserve honest feedback in the form of grades.

Privilege is a flip side to this. Many people whose lives and outcomes are boosted by privilege face the same problem of disconnect between effort and outcomes. Often their success had little to do with their efforts and a lot to do with the privilege they inherited. Considering that approximately 57% of Harvard students come from families in the top 10% of the income distribution, it is clear this is relevant give the grade inflation there.

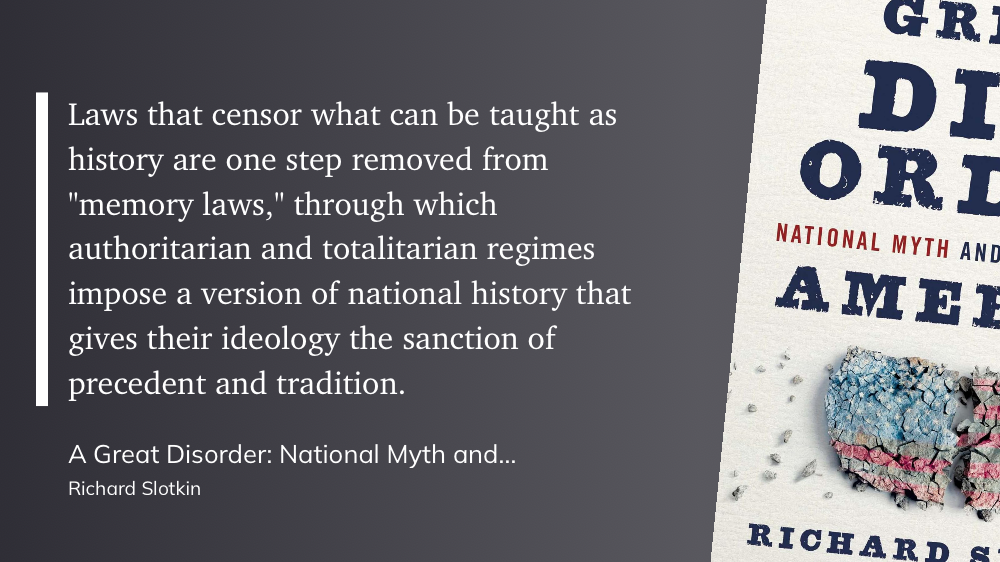

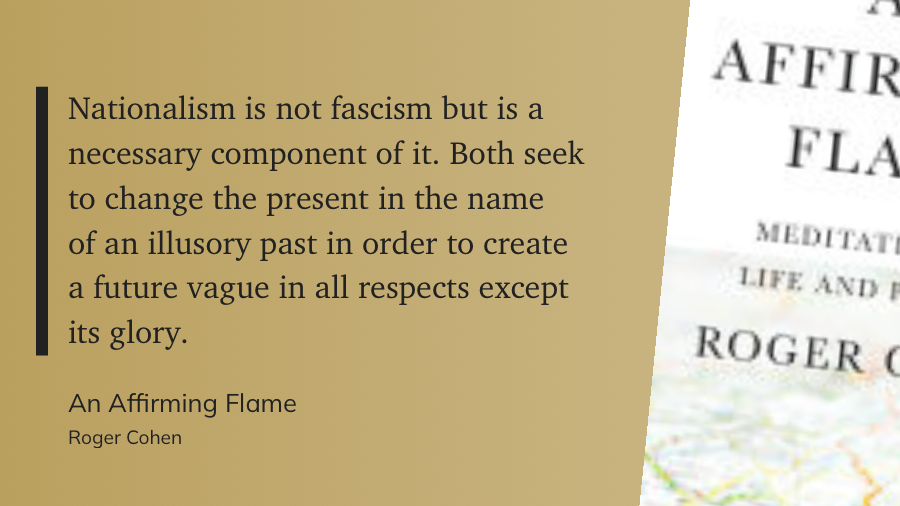

Patriotism trumps Nationalism

In my APUSH classes today we wrapped up the War of 1812 and began a lesson on the surge of nationalism that arose in the young United States in the wake of the war. To help differentiate nationalism from patriotism, I shared the quotes below from Roger Cohen’s excellent, thought-provoking book An Affirming Flame and encouraged students to discuss them.

My students got Cohen’s points immediately, and I think it is safe to say they agree with Albert Einstein that nationalism is an ‘infantile disease’ that leads to war and is primitive and unbecoming of grown ups in this day and age. Many of us can see that now. However, nations as political constructs are not all that old and despite the fact that in the early 1800s the Napoleonic Wars were raging in Europe, the horrors of the two world wars lay ahead of everyone. The nationalism that arose in America during and after the Era of Good Feelings had many contributing factors (such as the Battle of New Orleans, Clay’s American System, Chief Justice John Marshall’s SCOTUS rulings, and developments in the arts) and in hindsight it is understandable why it arose. However, surely it is time to put the ridiculous ideology to bed and replace it with an openhearted patriotism and general goodwill towards others.

Demographics of a Dysfunctional Legislative Branch

We are looking at Congress as an institution in my AP Government class at the moment. In order to allow students to see the demographics of Congress relative to our society, I provide the official report that Congress makes available and ask student to do a bit of research. Below is a demographic summary of Congress, in all its dysfunction. Note, this does not include the recently elected Democratic congresswoman from Arizona Adelita Grijalva.

- Party breakdown (May 13, 2025): • House: 220 Republicans (plus 3 Delegates), 213 Democrats (plus 2 Delegates and the Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico), and 2 vacant seats. • Senate: 53 Republicans, 45 Democrats, and 2 Independents (both caucus with Democrats).

⸻

- Women in Congress: • 155 women serve (129 in the House, including 4 Delegates; 26 in the Senate). • They make up 28.65% of total membership. • Women make up about 50.5% of the overall U.S. population, so they remain underrepresented.

⸻

- Average age: • House: 57.9 years • Senate: 63.9 years • Median U.S. age: about 39 years (U.S. Census 2024). → Members of Congress are much older on average than the general population.

⸻

- Most common professions: • Law, business, and public service/politics. → In contrast, the most common U.S. jobs overall are in retail, food service, and office administration—showing Congress is dominated by professionals rather than service-sector workers.

⸻

- Education: • 96% of Members are college graduates; 66% of House and 78% of Senate members hold advanced degrees. • By comparison, only about 38% of U.S. adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher—so Congress is far more highly educated than the general population.

⸻

- Average length of service: • Representatives: 8.6 years (about 4.3 terms) • Senators: 11.2 years (about 1.9 terms) → A more experienced Congress can mean institutional knowledge and policy expertise, but can also reduce turnover and fresh perspectives. Conversely, many newcomers can bring new ideas but may lack legislative experience.

⸻

- Religious affiliations: • 55.1% Protestant, 28.0% Catholic, 6.0% Jewish, 1.7% Latter-day Saints, small numbers of Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and Orthodox members. • Compared to the U.S. population, which is about 63% Christian and more religiously diverse overall, Congress remains more heavily Christian.

⸻

- African American Members: • 61 in the House (including 2 Delegates), 5 in the Senate → 66 total (12.2%). • African Americans make up about 13.6% of the U.S. population, so representation is roughly proportional.

⸻

- Hispanic or Latino Members: • 50 in the House (including 1 Delegate and the Resident Commissioner), 6 in the Senate → 56 total (10.35%). • Hispanics/Latinos make up about 19% of the U.S. population, so they remain underrepresented.

⸻

- Asian American and Pacific Islander Members: • 24 total (21 in the House, 3 in the Senate) → 4.4% of Congress. • Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are about 7.5% of the U.S. population, so they are underrepresented.

⸻

- Native American Members: • 4 total (3 in the House, 1 in the Senate) → 0.74% of Congress. • Native Americans are about 1.3% of the U.S. population, so they are underrepresented.

⸻

- Military service: • 98 Members (18.1%) have served or are serving in the military. • This is down sharply from 64% in the 97th Congress (1981–82) and 73% in the 92nd (1971–72). • About 6% of U.S. adults are veterans today—so Congress still has a higher veteran rate than the general population but much lower than mid-20th-century levels.

5 Recommendations

This is a beautiful translation of the Buddha’s timeless wisdom. The introduction is sublime.

- Getting Yelled at By Dumbasses blog post on How Things Work Substack

Came across this blog post recently and agreed wholeheartedly. Thought the message should be shared.

- Goose - State Of The Art (A.E.I.O.U) [feat. Jim James] - 9/24/25

Goose does a lot of great covers. They’ve been coving this song by My Morning Jacket for a while. Indeed, I saw them do it at my first show. Thing is, I didn’t really dig Goose’s version. This recent version has MMJ lead singer Jim James doing the singing. Much better!

- Documentary about the Dead in the fall of ’73, The Two Towers

This is probably for hardcore Deadheads only. A raw, honest look at the band in the fall of 1973. Primary source Grateful Dead historiography!

This is a cool AI tool. I use it personally but am increasingly using it for teaching, as it is now embedded in Google Classroom. If you are a high school teacher, you need to check this out.

Judging the Past

In three of my classes today we had a Socratic seminar on an essay by historian Douglas Wilson about Thomas Jefferson called Thomas Jefferson and the Meaning of Liberty. The essay is almost 30 years old and is a bit out of date with regards to Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemmings. Nevertheless, Wilson makes some interesting points about how modern Americans should think about viewing figures such as Jefferson, whose lives contained such glaring contradictions.

One of the specific points Wilson makes has to do with the idea of presentism, which he describes as judging those in the past through the lens of our modern societal norms and values. It is always an interesting idea to hear teenagers discuss. Often in years past students were quick to dismiss the logic of avoiding presentism. With ‘cancel culture’ on the rise, students often self-righteously condemned imperfect historic figures such as Jefferson and James Madison. Indeed, learning of Dr. King’s infidelity was often a hard blow for many of my former students.

However, in today’s discussions I noticed students were generally more wary about judging too harshly. It wasn’t that they couldn’t and didn’t call Jefferson out. They did. However, I was impressed to see that those students who spoke often articulated a nuanced take that both recognized Jefferson’s obvious moral hypocrisy, as well as the fact that historical figures are and were regular people and always far from perfect. It struck me because such nuance was often missing from discussions of this essay in the past. Indeed, students today recognized that social media has made it easier for people to judge others, both their contemporaries and historical figures. They noted that this was not a positive development.

At the end of the day, I felt good about the conversations we had for a lot of reasons. I especially appreciated the more sophisticated reading of Wilson’s argument about presentism. Indeed, a lack of nuance is present in the debates of the adults in our society nowadays, so I was happy to see young people going there. It will help in the coming days and months as they eventually take a look at Kermit Roosevelt’s take on the Declaration, American Revolution, and Reconstruction amendments.

Red Stockings and Trolley Dodgers

I am teaching a new elective class this year called American Sports History. One of the many benefits of teaching a new class is that I get to learn a lot. The early history of baseball was one of our early topics and while teaching I came across the origins of some team names that I had always wondered about. This was great because I am a huge sports fan. It was also cool because I often bring up team names while teaching history since so many names are derived from historical connections with their cities and regions. Obvious examples include; the New England Patriots, the Philadelphia 76ers, the San Francisco 49ers, and the Portland Trailblazers. When I point these out in class I get the pleasure of seeing many lightbulbs go off.

The origin stories I recently learned about have to do with the Cincinnati Reds and the Los Angeles Dodgers. I always wondered why a midwestern team would have a name associated as a political slur. Their original name was the Red Stockings, and they are considered to be America’s first professional team. They became the Reds eventually, but during the early days of the Cold War, they did actually change their name from the Reds to the Redlegs. They changed back to Reds in 1959.

Most baseball fans know that the LA Dodgers started in New York and were known as the Brooklyn Dodgers. But dodgers of what? Seems like a random team name. Apparently, before they were the Dodgers, they were the Greys, the Bridegrooms, and the Robins. In the 1930s, with trolley’s becoming ubiquitous, they were renamed the Trolley Dodgers. They eventually moved to the West Coast, and the local connection of the name became shrouded to most.

For the record, the original names (and locations) of my favorite teams are:

Athletics: Philadelphia Athletics (1901-1954) → Kansas City Athletics (1955-1967) → Oakland Athletics (1968-2024) → (Sacramento) Athletics (2025-2027, temporary while new stadium built) → Las Vegas Athletics (2028-present, planned)

Raiders: Oakland Raiders (1960-1981) → Los Angeles Raiders (1982-1994) → Oakland Raiders (1995-2019) → Las Vegas Raiders (2020-present)

Kings: Rochester Royals (1945-1957) → Cincinnati Royals (1957-1972) → Kansas City-Omaha Kings (1972-1975) → Kansas City Kings (1975-1985) → Sacramento Kings (1985-present)

Stanford Cardinal: Stanford University, Stanford, California (1891-present) - The team name changed from “Indians” (1930-1972) to “Cardinal” (1972-present), referring to the color cardinal red, not the bird.

They Can't Scroll Us Away

One of the hardest parts of teaching is covering topics that don’t naturally interest most 16- and 17-year olds. Some folks, mostly those that aren’t actually trying to educate young people, claim that the job of teachers is to make topics ‘interesting.’ This sort of cant grates. The fact is, sometimes young people need to be made aware of realities that—on a Tuesday afternoon in October—they won’t easily engage with. This has always been a dilemma for teachers (portrayed humorously by SNL back in 1992), but it is made even more problematic in the Age of Handheld Distraction. Teens today are used to watching a short video on their smartphones and scrolling past it within seconds if it doesn’t capture their interest. And teachers are not entertainers. Students can’t scroll us away.

The quote below by educator Peps Mccrea resonated with me because it’s true and because it isn’t something teachers hear all that often. If math was intrinsically interesting to 8 year olds, schools wouldn’t be needed. Indeed, algebra is not always a ‘magnet of attention’ for most people, kids or otherwise.

In my case, I recently taught Brutus No. 1, the most famous of the Anti-Federalist arguments against the ratification of the Constitution. It was written in 1788. It comes off as stilted to the modern reader. It is—Hard. To. Read. Of course, the arguments Brutus made about an overpowerful federal government ruled by a strongman is super relevant to teenagers growing up in Portland, Oregon at the moment. That depressing fact of life today helps make the reading relevant. But the point remains: it is not necessarily interesting (as evidenced by the fact that the vast, vast majority of Americans have no idea a) what Brutus’ arguments were and b) who the Anti-federalists were). Indeed, those who do know it most likely learned it in school.

So, the dilemma remains. We have to teach topics that aren’t always going to interest students, that aren’t natural ‘magnets of attention.’ The art of teaching–the perpetual challenge–is figuring out how to make even the dullest topics come alive for as many students as possible.

What My Students are Grateful For

Every Friday, after their weekly quiz, I have my students complete a Google Form that I call a ‘Self Assessment.’ I ask them how their week went and various related questions. I also ask them early on to tell me something they are grateful for. I am a big believer in noticing what we are grateful for because I believe it helps train the brain to become a seeker of such things.

The top five categories were: 1) Family 2) Friends (a close second) 3) Pets (more family!) 4) Music (🤘🏻) and 5) Food (a bit surprising, but hey, it makes sense).

This week God got a few shoutouts, but less than school related elements (such as quiz retakes and ‘enjoyable classes’).

Some memorable answers:

“I’m grateful to be alive, because I know being alive is even something so rare, that I should appreciate it every day.”

“The ability to listen to any recorded song from any point in history with just my phone for the price of 1 subscription.”

“Stevie Wonder”

“EVERYTHING!!! My life, family, air, every single thing.”

Pretty cool.

Tyranny of the Majority—and the Minority: Federalist No. 10 and the Fate of Liberty

In my AP Government class we recently read Madison’s Federalist No. 10. Rereading it this year, I am reminded that it is something I wish more Americans were familiar with and the conversation in class connected to an idea in one of the books I just finished reading. In Federalist No. 10 Madison argues for a republican government; that is, a representative democracy. His fear of majority rule (‘direct democracy’) was based on the idea the majority might use that status to trample on the natural rights of the minority. He was mostly worried about the landless masses taking the property of men like himself through the power of the legislature. However, his point has been made throughout American history. The example I use in class is the stain of Jim Crow racism in our history. For close to 100 years a majority of whites in many states (and in all the southern states) voted to trample the rights of non-white citizens. They disenfranchised racial minorities as well, but even if everyone in those places could actually vote most southern states were still majority white so Madison’s point would have likely still been made, that in a pure democracy there is a danger of the minority having their rights abused. This is known as the ‘tyranny of the majority’ and it is an obvious danger of a direct democracy.

Of course, a minority faction (that is, an interest group or political party that does not represent the majority of society) can also trample on the natural rights of the people if they have power. Today, we certainly can see that those with enormous wealth, a minority for sure, have captured much of our government and take advantage of that capture to protect their wealth (I’m looking at you 119th Congress). While discussing the essay, students in class brought up campaign finance as an example of a faction’s threat to our democracy. Coincidentally, their comments touched on something I recently read.

The Narrow Corridor is an excellent, if wonky, book, subtitled ‘States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty.’ At the end of the paradigm-shifting book, the authors (Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson) include a few suggestions for keeping America ‘in the corridor’ (between a ‘despotic leviathan’ and an ‘absent leviathan’), as it is clear to everyone paying attention that we are living in a time when liberty is being threatened by an increasingly unshackled state.

So what was the connection? Well, the first solution Acemoglu and Robinson mention was campaign finance reform. Specifically, they argue we should “curtail campaign contributions and limit the impact of lobbying. Specific measures to bring greater transparency to the relationship between firms, lobbyists, and politicians may be particularly important since accounts of how politicians became become faithful servants of certain industries or interests often involve meetings hidden from the public eye and poorly monitored revolving door arrangements in which regulators and politicians are later hired by the private sector at very attractive salaries.”

In other words, it would be beneficial to change our campaign finance laws in order to make it harder for minority factions (that is, special interest groups) or the uber-wealthy in general, to threaten the liberty of the majority of citizens.

I always love it when something happens in class that connects with something that has been brought to my attention by something I have recently read. I wonder what Madison would say about the fact that today such a small minority, due to their incredible wealth, can manipulate our government, at all levels, for their own benefit.

Moving Targets

Sam Wineburg is one of the brains behind the amazing website Digital Inquiry Group (which used to be called the Stanford History Education Group). The team behind DIG produces high-quality lesson plans for social studies teachers that focus on inquiry and expose students to a variety of primary and secondary sources. Their lessons also emphasize that there can be multiple views about what has happened in the past. I have happily used their lessons for years.

A few years ago I read Wineburg’s excellent book Why Learn History. The quote below resonated because it gets to an issue that the public, and many educators, aren’t familiar with. Namely, that the folks who make the tests are constantly redefining what counts, which makes the tests a bit less helpful than they could be. In Oregon, students’ knowledge of social studies content isn’t really tested. Certainly, if students are taking AP exams, they are taking standardized exams written by the College Board. However, as a veteran educator, I don’t put a lot of trust in their test results. The main reason for this is that test scores can yo-yo from year to year, even though what and how I teach isn’t all that different from year to year.

Moving the goal posts leads to another issue. When students demonstrate mastery of a particular skill or fact, that item might vanish from the test, not because it’s unimportant, but because assessors want to maintain a spread of scores. That practice means success can feel like it gets punished—today’s knowledge may not even register tomorrow. At the same time, it’s worth noting that there are moments when standards are lowered, which is an entirely different problem. Lowering expectations masks gaps rather than addressing them, creating a false sense of progress. Between shifting targets on one end and diluted benchmarks on the other, it’s little wonder that educators, parents, and the public often struggle to trust what standardized scores actually tell us.

On top of that, when I think about my own teaching, it is an absolute fact that I have gotten better as my career has continued. I’d say the quality of teaching generally is better than what one would have found broadly twenty-five years ago. We just know more about good instruction. Yet, the news and ‘scores’ don’t always reflect it.

At the end of the day, as both a teacher and a parent, I don’t put too much weight into test scores. I’m not opposed to standardized tests, but I try to keep in mind Wineburg’s point, that there are reasons, often hidden, that weaken their ability to inform.

Start Today: What Ryan Holiday Reminds Us About Time

As a teacher, I hear students lament the frustrations of procrastination all the time. Just last week I asked some of my classes during a whip around what they want to improve on this semester. The most common answer was beating procrastination. Of course, teenagers aren’t the only ones who battle this problem. Steven Pressfield wrote a beautiful book about it called The War of Art. He called the problem The Resistance.

Fellow writer (and Pressfield friend) Ryan Holiday provides a helpful perspective on procrastination in the three sentences shared below. Whereas Pressfield frames procrastination as fear dressed in all of our endless distractions, Holiday goes a bit further and says it is arrogance. Together, they show both the inner and outer faces of the same issue.

I couldn’t save this quote into my second brain fast enough. It gets to the heart of the matter for me because it relates to the core Buddhist idea of impermanence. When I remember that nothing is guaranteed, not even tomorrow, it makes the decision to start today feel less like a burden and more like a responsibility. It is a fact that we could die at any time. Karma can shift on a dime. Most of us don’t think about that fact very often (that’s a whole other topic). Thus, Holiday is spot on; to put something important off because you think you will have time later is arrogant. It’s also true that if you lack the will and the discipline in the present, what’s to say you’ll have it in the future? For me, this shows up most clearly when I put off my short little home weight lifting protocol. I tell myself I’ll do it in an hour, but half the time it never happens that day.

Readwise, the app I use to capture these quotes while I read, allows you to pick favorites that they email to you every Sunday. This is one of those favorited Sunday quotes for me.

5 Recommendations

-

NYT Sunday Routine feature I love this weekly feature in the New York Times. It spotlights a random New Yorker and lets them walk the reader through a typical Sunday. I like that it illuminates the lives of everyday people and I have also found that I enjoy seeing both what people’s the inside of peoples’ homes look like and how they spend their time. It is behind the NYT paywall.

-

Short documentary The Evolving Mind of Neil Peart This video showed up in my feed because I love Rush. It was published in early September 2025 but is evergreen if you are a Rush fan or interested in their amazing drummer. This short documentary takes a look at some the philosophical ideas that are often associated with Peart, especially his early song writing.

-

Ghost Rider book Thinking of The Professor, I immediately thought to recommend his wonderful book Ghost Rider. Peart’s wife and only daughter both died in the same year and in order to cope with the loss he jumped on his BMW motorcycle and drove all over North America, from Alaska to Mexico and all points in between, both east and west. It is part travelogue and part meditation on death. Five out of five stars!

-

Book Developing Curriculum for Deep Thinking This is a recommendation for those in education. For years, the dominant view in teaching is that we should be doing ‘higher level thinking.’ You know, ‘synthesis’ and ‘analysis’ and ‘evaluation.’ Well, yeah, those are practices we want our students to be familiar with and to be comfortable engaging in. However, sometimes students don’t have the foundational knowledge to engage in these ‘higher’ levels of thinking. You can’t connect the dots, if there aren’t any dots. This short book is a breath of fresh air in its advocation for a curriculum that is deeply rooted in factual knowledge.

-

Peps McCrea’s teaching email newsletter Mr. McCrea is a British educator with a great, research-based newsletter for teachers. The emails are short and sweet with links to the research.

As I embark on my 28th year of being a high school social studies teacher, and in our current political context, I have enjoyed looking through my Readwise collection of quotes about the importance of what I do. Here are a few ideas shared without further commentary.