My Reading & Thoughts

Winter Has Begun

The winter solstice is a big day on my calendar. So much of what Christmas has become is really a celebration of the fact that the darkest day of the year has been reached, and that more light is coming, despite the days continuing to grow colder. The evergreens in our homes, the lights on the trees, and the candles and their atmospheric wonder help us cope with the mugging by the dark and the cold. I love it and I love that the days slowly get longer. Indeed, it is an element of the winter and spring that I most appreciate.

Here are some beautiful poems about winter.

Wendell Berry’s To Know The Dark

And some music…

He Does Not Forget

We dropped our cat off at the kennel today and that got me thinking about cats. That led me to J.R.R. Tolkien’s poem ‘Cat’ which beautifully juxtaposes a domesticated cat with it’s wild ancestors. The poem appeared not in one of Tolkien’s most famous novels, but in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.

but fat cat on the mat

kept as a pet

he does not forget.

Life is Aperiodic

I just came across a concept that was new to me, the concept of being aperiodic. Technically, ‘aperiodic’ describes something that does not repeat at regular intervals. More precisely, it describes a system, pattern, or process is aperiodic if it lacks a fixed cycle—there is no consistent period after which it repeats exactly. A common example that we all learn about in school is the number pi. Another example is the tiling pattern known as the Penrose tiling pattern. Mathamatically, what is cool about this is that an aperiodic thing can still have structure, order, or rules, just not repetition.

Upon reflection, it is clear that life is aperiodic. I think we crave cycles because they feel safe: routines, habits, three-year plans. But our lived experience rarely cycles neatly. Even when days look similar on the surface, our interior weather keeps changing and the details are always a bit different. The same evening stroll hits differently depending on worry, hope, hunger, or sleep. Hearing the same song lands with a new weight. There is pattern, yes; but not repetition.

This makes me realize that it is okay if an open loop doesn’t always close when or how I expected. I want to pay more attention to the variations in the pattern of my day to day. Is that not where some of the wisdom hides, in the differences?

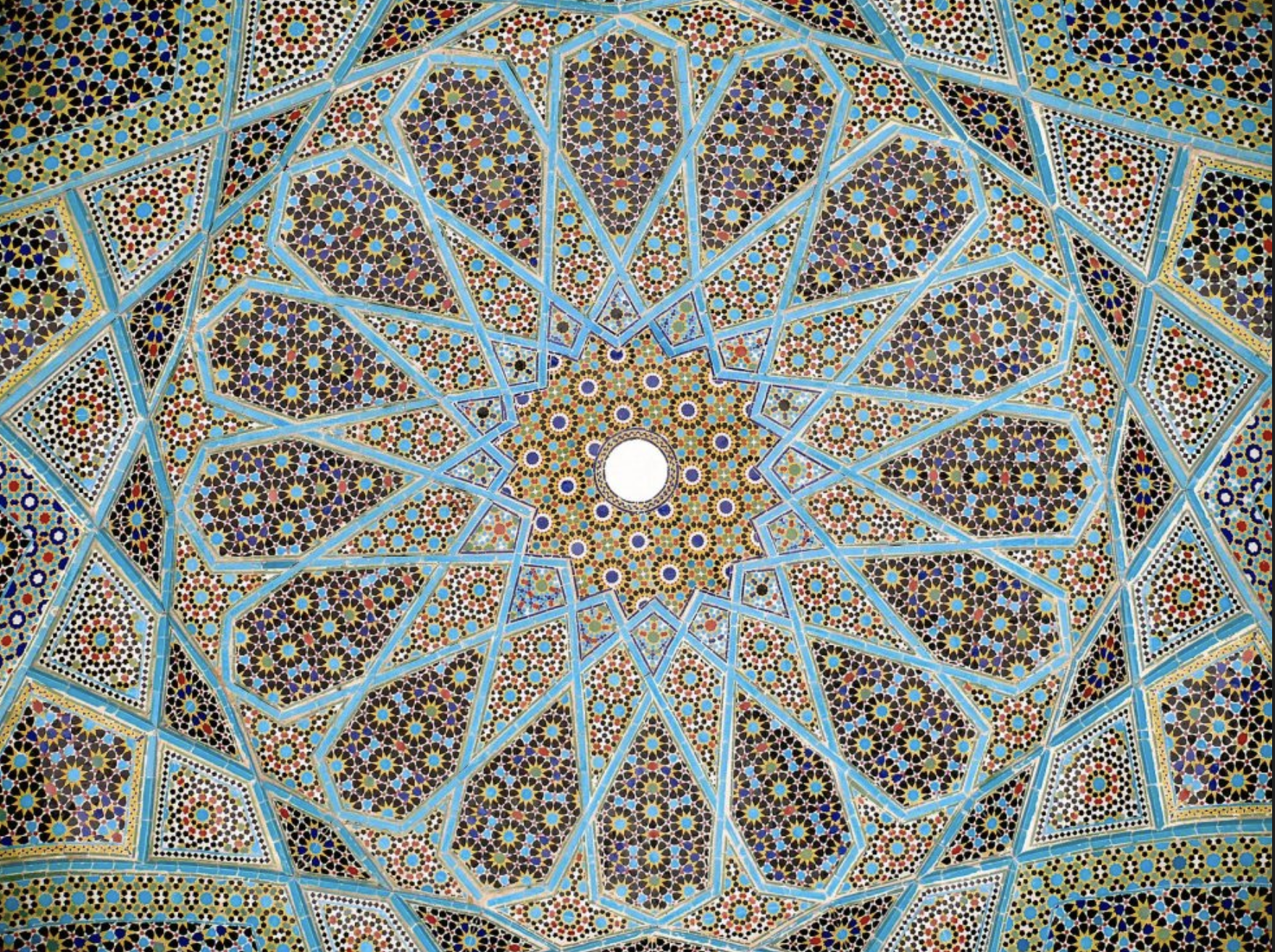

Iranian glazed ceramic tile work, from the ceiling of the Tomb of Hafez in Shiraz, Iran. Province of Fars.

Some Quotes from Ryan Holiday

Ryan Holiday is one of my favorite writers. I can’t recommend his books enough. Here are some great quotes from a few of his books.

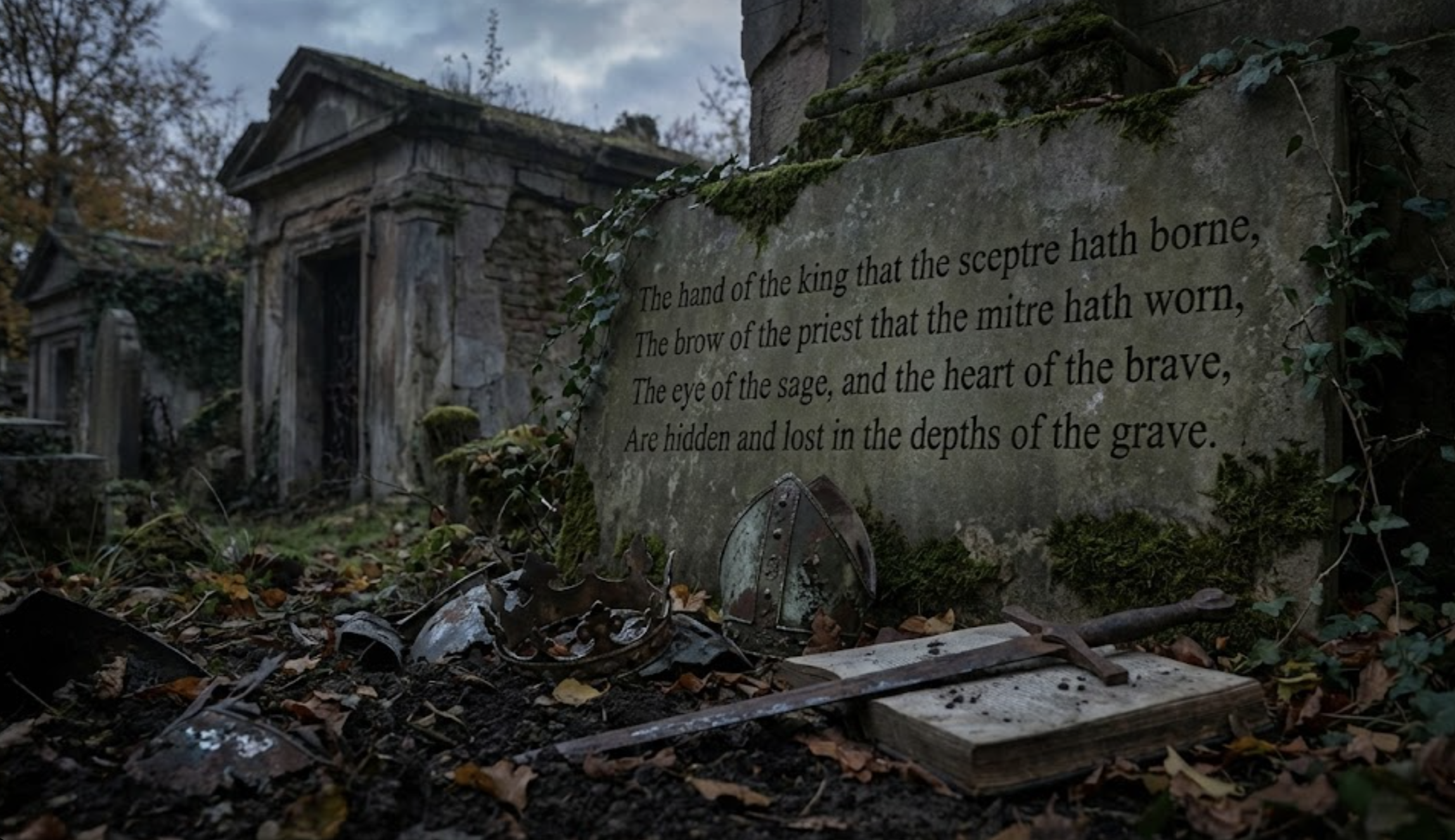

Mortality

I had never heard of the poet William Knox until I came across his name in Jon Meacham’s excellent book And There Was Light, which is about Abraham Lincoln and his spiritual beliefs. Apparently, the poem was one of Lincoln’s all time favorites. The poem is called Mortality. I looked it up and consider it a wonderful nod to memento mori; an always welcome reminder.

Don't Buy It & Create Your Own

I came across the first quote below by Morris Schwartz in Paul Millerd’s book The Pathless Path. What strikes me about the quote is twofold. First, I agree wholeheartedly that our culture is essentially sick and emphasizes many foolish ideas. The Terrence McKenna quote below (lifted from Tao Lin’s excellent memoir Trip) makes this point even more pointedly.

Secondly, agreeing as I do with both Schwartz and McKenna, I feel challenged to follow Morris’ advice to make my own culture as an antidote to living in such an unwell society. Upon reflection, I feel like I have quite a bit of work to do in this regard. I have managed to cut myself off from social media. I also watch virtually zero traditional TV, unless it is an interesting college football game. I have a subscription to Netflix, but I probably watch one show about every 4 months. I suppose my daily commitment to reading is also an attempt to cultivate my own mental universe.

Indeed, all of these elements of my media diet have helped in many ways. However, I still spend too much time on YouTube and too much time generally following politics. I also don’t vote with my wallet as consistently as I should, which I also see as a means of standing athwart the dominate culture and trying to make a small difference.

As I type this, I realize I am going to have to keep thinking about this particular question. This earlier blog post of mine is a stab at solving this puzzle. However, I simply don’t have many other answers appearing to me about how to follow Schwartz’s injunction. It is a worthy goal though, rejecting the powerful yet vapid parts of American society to carve out one’s own niche, and hopefully, improving the general culture action by action.

Inner and Outer Maps

A cool new feature of Readwise is that is can send you a weekly email that combines four or five quotes from your collection that are related in some way. These four quotes all shed light on both the inner and outer maps of ‘the world’ we inhabit.

MMT, Ray Dalio, and Gemini 3

The latest book I have started reading is a book called The Deficit Myth by economist Stephanie Kelton. The book argues in favor of what is called the Modern Monetary Theory. I was vaguely aware of the theory and decided to read the book so I could understand it better. Right off the back I thought about Ray Dalio’s ideas, as expressed in his books about the debt cycle, which I’ve read and enjoyed.

Now, I’ve been playing around with Gemini Pro lately, which gives me access to their latest AI model Gemini 3. So I decided to ask Gemini to explain what Kelton and Dalio might say to each other about the national debt. The results were interesting so I thought I’d share them here. As you’ll see, I asked a few follow up questions. I absolutely love that I can share the thread with others like I am doing here.

To read the thread, go here.

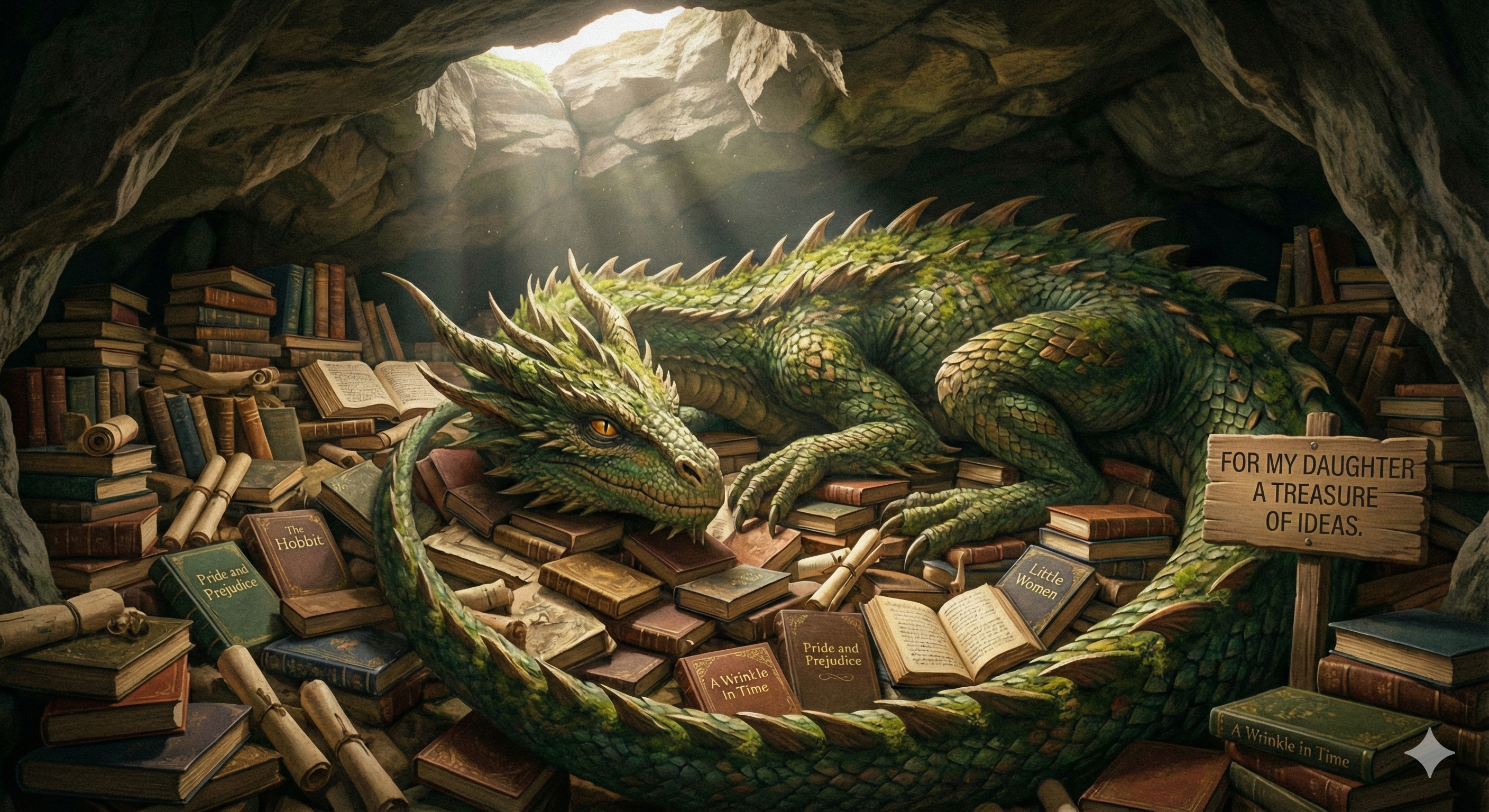

Ten Books I Hope My Daughter Reads Someday

I hope my daughter reads tons and tons of books. She is a pretty big reader as a middle schooler, so I think she is well on her way. There are some books of course, that I hope that she one day reads. I decided to come up with a list of 10 that I especially hope she gets to. My guess is this is the type of list that will always be changing, based on where I am at in my life. However, for the record, here are the ten I thought of today. Please note, The Lord of the Rings is not on the list because I had the distinct pleasure of reading the whole thing to her when she was younger.

- Meditations, by Marcus Aurelius

2 to 5. Ryan Holiday’s Cardinal Virtues series

-

Eknath Easwaren’s translation of The Dhamapadda

-

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

On William Penn

Most of us remember that Pennsylvania was founded and named after William Penn. Many will also recall that Penn was a Quaker and that the Quakers were a Protestant Christian sect that were pacifist and later played an important role in the abolitionist movement and the underground railroad. Oregonians may know that one of our local universities is named after the leading Quaker George Fox.

Penn comes up in my AP US History class when students are learning about the unique attributes of the original British colonies in America. I always talk a little about the Quakers and note that the city of Philadelphia derives its name from the Greek words for ‘dear’ or ‘loving’ and ‘brother.’ Hence, the ‘City of Brotherly Love.’ Very Penn.

I also instruct my students that Penn was relatively warm to the indigenous tribes. His general kindness backfired however, in the sense that migrants to the colonies found Pennsylvania relatively welcoming since the founder was so tolerant. The result was, after Penn’s death, the arrival of many who were not so tolerant, ultimately dooming the Native peoples to similarly frustrating sorry relative to the other parts of British North America.

However, I recently learned through my reading that Penn actually took the time to learn the language of the Lenni-Lenape (Delaware) people in order that he would be able to more fairly deal with them (he already knew five other languages, including English). Penn removed the middle man, hoping for deeper understanding and more fair dealing. I found this to be quite incredible, given what we know about the other colonists and their general greed and avarice. Indeed, Penn’s respect for the natives led to the so-called ‘long peace’ in Pennsylvania which lasted throughout his lifetime.

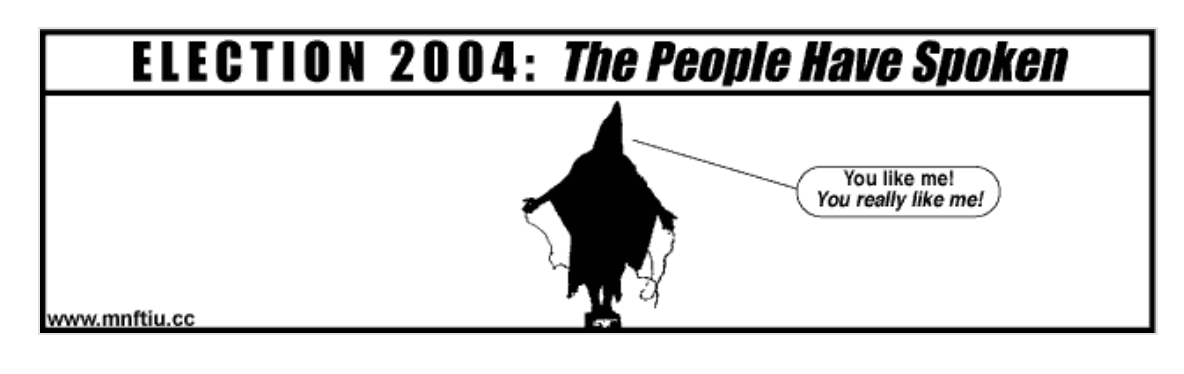

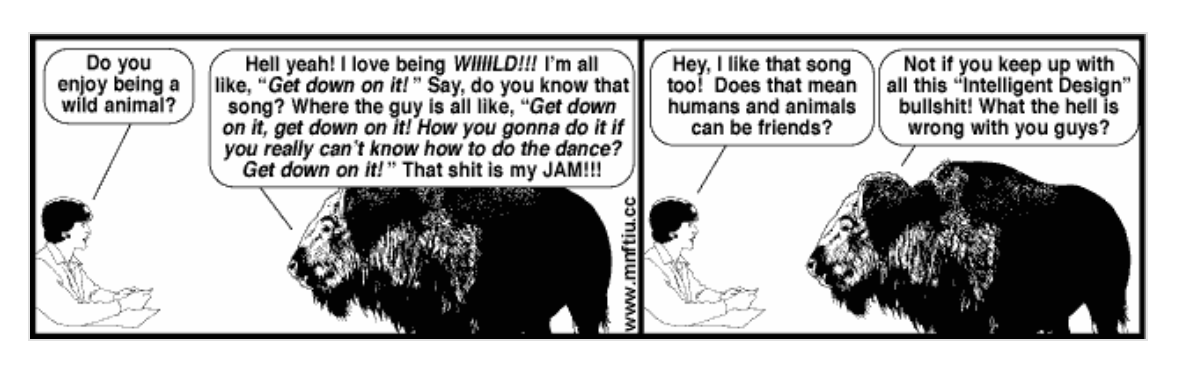

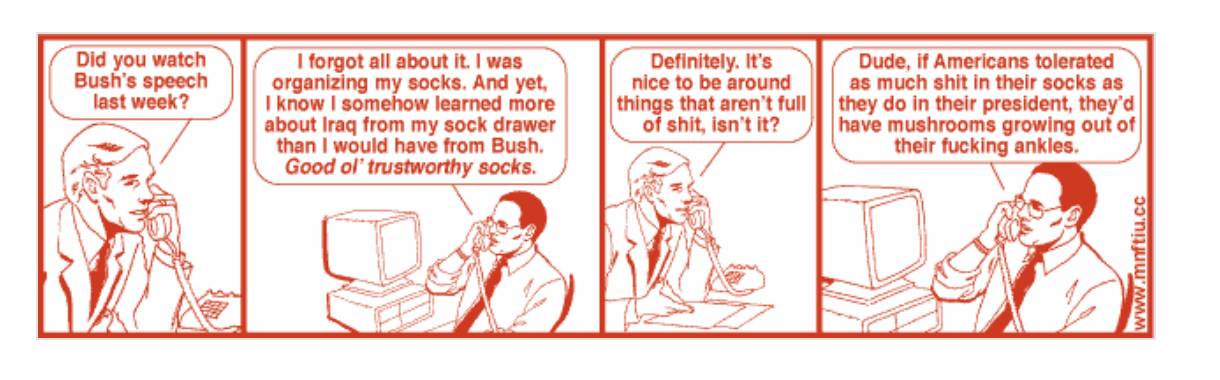

Where is David Rees When You Need Him?

Back when George W. Bush was the president there was a cartoon published in Rolling Stone called Get Your War On. I absolutely loved it. It was created by a very clever, and funny guy named David Rees. The deeply sardonic cartoon used corny office clip art to sarcastically skewer Bush and his fundamentally stupid policies, including the ‘War on Terror.’ The cartoon ran from October 2001 to the end of Bush’s presidency in early 2009. I thought of it because as I recently finished Ben Burgis' book about Christopher Hitchens, it occurred to me how much we need the wit and wisdom of a guy like Hitch in these times. It then also occurred to me that I wish Mr. Rees was making a Trump era version of Get Your War On. Maybe he could call it Get Your Greed On? Or maybe Get Your Corruption On?

Anyway, here are few of Rees' brilliant cartoons.

On Christopher Hitchens

I am reading an interesting book about one of my intellectual heroes, the late Christopher Hitchens. The book’s author, coming from the political left, argues that Hitchens got a lot right, but erred seriously in his support for both the “War on Terrorism” and the Iraq War during the first decade of the 21st century. Hitchens began his intellectual journey as a socialist and by 2004 was oddly all in on Bush’s foreign policy in the Middle East. The author also critically deconstructs some of the arguments Hitchens' made in debates about religion.

A couple points come to mind as I reflect on Hitchens and his thinking. For one, his mistakes make him more—not less—useful to thinkers today. The book emphasizes that studying where Hitchens went wrong sharpens our own judgment. Heroes aren’t templates; they’re case studies. His intellectual courage, eloquence, and range remain valuable, but so do the cautionary lessons that grew from his rhetorical confidence and general arrogance. Additionally, I am reminded that admiration doesn’t require full agreement about everything—especially with complicated figures like Hitch. Indeed, there is no one I likely agree with on everything. In my mind, Hitchens' error about Iraq does not tarnish his overall body of intellectual work. For instance, I love his book god Is Not Great, but thought his attacks on Buddhism to be feeble and a wasted effort.

But none of this diminishes Hitchens' importance. If anything, it makes him more useful. Hitchens shows us that admiration doesn’t always require absolute agreement and that inspiration doesn’t require perfection. For me, he remains a case study in how a thinker can be both brilliantly right and consequentially wrong—and still worth reading, wrestling with, and learning from.

Odd and Unpredictable

Bruce Dickinson is one of the most fascinating people in the world. He is most famous for being the long time lead singer of Iron Maiden, one of the best heavy metal bands of all time. However, in addition to that, Dickinson is also an author and a pilot, eventually flying the band around the world on their tours on their plane, Ed Force One. He is also a world-class fencer! His wide-ranging intellectual interests can be seen in the songs he has written over years. For instance, Alexander the Great is a great history lesson and Rime of the Ancient Mariner a great homage to Coleridge’s epic poem of the same name. Hell, I was first introduced to the novel Dune because of Maiden’s tune To Tame A Land.

The quote below is from his memoir What Does This Button Do? I saved it because I thought it was a great sounding sentence. I also saved it because I manages to convey a complex reality, very neatly.

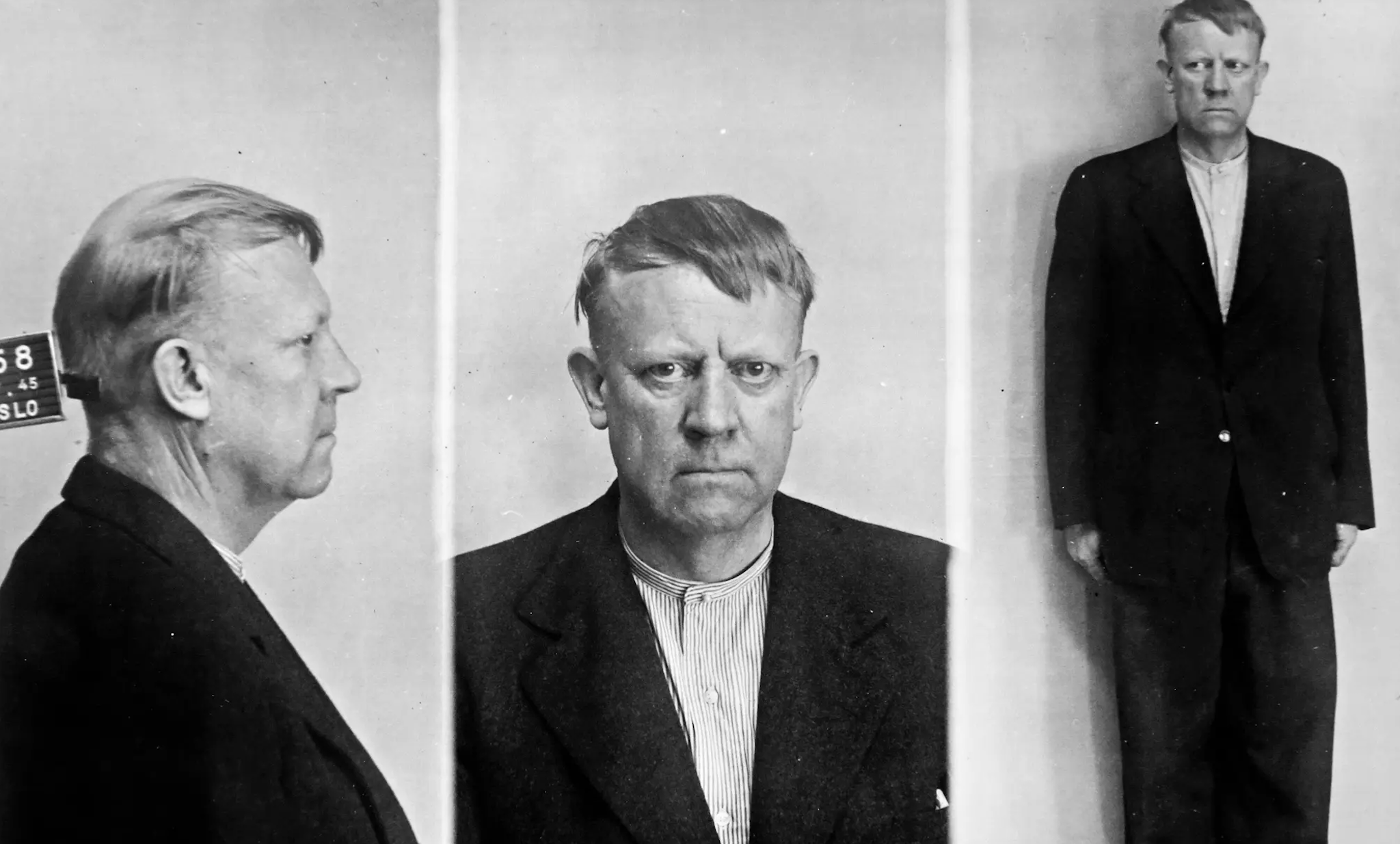

What or Who is a Quisling?

In Diane Ravitch’s memoir An Education, which I am thoroughly enjoying (!), I came across a word I was not familiar with. The word is ‘quisling.’ Chat bots being my new reading companions, I quickly looked it up.

The word is of relatively recent vintage, being coined during World War II. Apparently, a Norwegian fascist named Vidkun Quisling collaborated with the Nazis in his home country during the war. Thus, the word refers to someone who betrays their own country, or own group, by collaborating with the enemy. Benedict Arnold came to mind immediately when thinking about this. Thus, a quisling is a traitor. **Great word! **

Not surprisingly, Quisling was put on trial after the war for a variety of crimes and was found guilty. He was executed by firing squad in October 1945 in Oslo. He was buried in an unmarked grade, and his surname now is equated with treachery. A fitting end, I’d say.

Shaka Zulu

I recently came across Shaka ka Senzangakhona in three different books over the past two weeks, and I found his story too striking not to share. I first came across him in The Narrow Corridor, where the authors discuss his unique military innovations and brutal, but successful leadership. A few days ago, he appeared in General Stanley McChrystal’s book On Character. McChrystal shared a story about how Shaka made his warriors dance on ground covered with sharp needles and if they flinched, they were executed. Finally, in The Birth of the Modern, he was brought up in the context of the history of southern Africa during the early 19th century, when he reigned. I love it when such serendipity pops up in my reading.

Anyway…born around 1787 and dying in 1828, Shaka became king of the Zulu in what is now KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa from 1816 to 1828.

What fascinates me is how he took a relatively minor clan and, through bold military, social and political reforms, built it into a dominant power in his corner of Africa. His success arose because he reorganised the Zulu regiments, introduced new weaponry and tactical formations, and absorbed neighbouring groups under Zulu rule.

At the same time, Shaka’s reign is drenched in blood and controversy. His mother’s death in 1827 triggered a wave of harsh decrees—including mass-executions, bans on planting or using milk, and demands of mourning—that turned many of his own people against him. He was also apparently so paranoid that his heir might depose him, that if any of his concubines became pregnant, he had them killed. Not surprisingly, he was assassinated by his half-brothers in 1828.

In my reading, I’ve found myself wondering: how do we reconcile the visionary-leader and the ruthless-tyrant in one figure? His life makes me think of people like Alexander the Great and Napoleon, who are often idolized, but who both caused tremendous suffering as a result of their military pursuits. I’ll continue to reflect on how each of the three authors portrays Shaka, as successful military leader and cruel tyrant, and invite you to do the same. How does his story challenge our ideas of leadership and legacy? What lessons (or warnings) does his rise and fall offer us today?

Some Thoughts from Retired General Stanley McChrystal

General Stanley McChrystal is a fascinating dude. I first learned about him when he was forced to resign by Obama in 2010 because of comments attributed to him and his staff members that were published in Rolling Stone. Leading up to that, I have learned that he was a top rate soldier, which explains why he was in charge of Allied forces in Afghanistan at the start of Obama’s presidency. His military career is undoubtedly honorable and exemplary.

He is also known for the fact that for many years while in the military he only ate one meal a day. Combined with his daily exercise regimen he developed a reputation, even amongst those in the military, as a Spartan.

I am currently reading his book On Character and enjoying it very much. McChrystal is clearly a thoughful guy and not easily pigeonholed. I find myself agreeing with most of his takes on the big issues he discusses in the book. Below are some of his thinking, which I found insightful and wise. The quotes are about religion (1), race (2 & 3), and the Constitution (4).

JFK was Overrated

President Kennedy often gets a lot of props from the American public. There are elements of his presidency that I admire, most notably the fact that his rhetoric was often inspirational. However, I believe he is one of the most overrated presidents in modern history. The obvious arguments have to do with his escalation of our involvement in Vietnam and his slowness to support civil rights. In recent years I have come across other examples that call into question his leadership. Some of these have to do with his behavior towards women (see p. 109 of Brian Lamb’s book The Presidents (where today’s quote is from). Another example is the one mentioned below. During the attempt by the Kennedy team to pass civil rights legislation, when they had LBJ at their disposal–the ‘Master of the Senate'-they preferred not to seek his help. Of course, after Kennedy was assassinated, LBJ got both the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act passed a year later, proving that Kennedy was foolish in failing to enlist his help.